I Pythia

I, Pythia

‘When desolation falls like a blight, the day for the worship of gods is past.’

- Euripides, The women of Troy

The high priest of Apollo, old Orisabios, had lived long enough to see the temples crack and their trappings fade, but he had one last hope. I was the girl he had chosen as Delphi’s final and desperate answer to the Christian’s virgin-born messiah. It was said that my mortal mother had been a virgin when the god Apollo, struck by her beauty, had lain with her. Previous Pythias had been mature women learned in politics and history - but in the final act of the sacred struggle, Apollo would speak with a new voice, through me. I knew that Apollo was my father, and that the mountain was my destiny. How often I had stared at the pink and gold face of Mount Parnassus in the rays of dawn, as a moth might stare at the flames dancing in the god’s bronze tripod.

Four bare armed young men chosen from the village so that their own beauty might also delight Apollo, carried me in a cedar wood litter wound about with laurel strands - the plant most sacred to the god. The winding path from the valley to the high sanctuary was worn by the feet of a thousand years. Ancient cedars lined its northern slope, forming a long green colonnade pointing the way to the heavens. Along its edges purple, pink and white cyclamens blossomed out of broken stones. In earlier times, throngs of people would have lined the route all the way from the village to the sanctuary, but Delphi had fallen on lean times. Pilgrims, ambassadors, priests, princes, kings, emperors and their armies had tread this way before seeking glory, blessings, and sometimes plunder. Delphi had been, in its long summer, as rich as it was holy. Only the Christian god claimed to love poverty, yet it was his holy places now that teamed with treasure.

Pythia, the name I shared with all my predecessors, was more ancient even than the god I served. I had learned the ancient lore of the gods of nature on my mother’s knee. Generations of gods changed, slower than those of men, but the earth is eternal. Before it was called Delphi, the holy place had been called Python, after the older god, the serpent son of Gaia. Delphi was the womb of the world. Here, mother earth’s children sprung forth and alone of them Python stayed to build a temple to his sacred mother. Apollo came one day like a comet on a dolphin's back, and slew him, just as his brethren overthrew the Titans, the older gods, that were themselves the children of the Earth and Sky, the mother and the father of all things. Apollo took possession of the sanctuary on the mountainside, and Pythia became his voice. It was said that when she listened, the Pythia could still hear vanquished Python hissing through the rocks under the temple.

Orisabios greeted me at the sanctuary gate. Marble sphinxes with inscrutable faces guarded its bronze doors. The sanctuary sat upon the slope between two arms of the mountain, in a natural amphitheatre facing south, a stage embraced by the soaring rock faces we called “Phaedriades” - the Shining Ones - reflecting the eternal westward dance of the sun across the sky. Marble sphinxes with inscrutable faces guarded its bronze door. Old women and their grandchildren made up the attendants of the sanctuary. Their hands reached out to touch me and voices whispered desperate and eager blessings.

I alighted and walked between flute and string players up the sacred stair, ascending between monuments whose glory seemed eternal. Here were the treasure houses of the old cities of Greece. Columns burst out of marble foliage towards blossoming capitals. Flowering ivy hung over holy rocks. What the sanctuary lacked in the living it made up with the presence of the dead. A thousand statues, likenesses and offerings of generations of pilgrims, gazed blankly at our procession from their engraved pedestals and shadowy gateways. The spirits of their makers were alive with me too that morning, as we processed along this hallowed way to Apollo’s great temple.

The marble dust of the temple columns sparkled in the sunlight. Garlands of laurel leaves and pink hyacinths - blossoms whose colours renew heedless of human devotion - were draped between its capitals. Above them on the temple pediment, the weather-worn figures of the god Apollo, his mother Leto, and his sister Artemis were arrayed in marble, in a chariot whose horses looked like they might leap out of the temple head and fly at the eastern arm of Mount Parnassus. Under the eastern portico, above the golden door, was carved in stone the motto of the Oracle - ‘Know Thyself’.

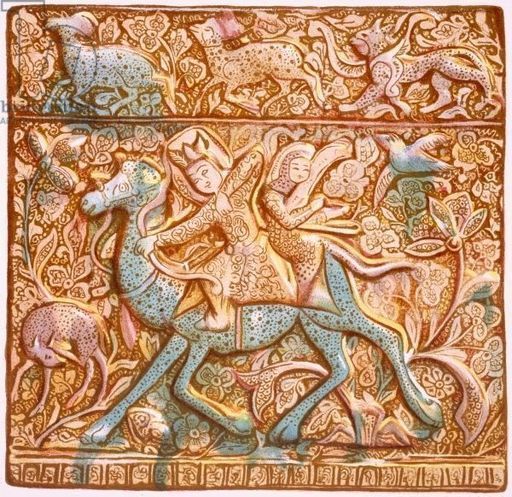

Within the temple’s inner chamber, among the blazing braziers hung from the iron talons of gryphons, Apollo’s priestesses danced in front of the god’s statue. Apollo stood as if entranced by their movements, his smooth and languid body draped casually in an ornamental cloth, a crown of laurel upon his head, one arm resting upon a lyre, the other outstretched and pointing as if at the mountain beyond the portico. With the god as witness, Orisabios set the crown of sacred laurel upon my head. I had my first taste of the fasting foods, the bittersweet blood of crushed pomegranates, the pungent spice of bay leaves and the bitter laurel ground between my teeth. I was taken in procession to the path above the sanctuary to drink and bathe in the virgin waters of the Castallian Spring.

Days of rituals lay between me and my destiny. At last, I sat in silence upon the ancient tripod stand in the temple’s cellar, where the darkness of the underworld met its first shafts of light. A narrow fissure ran through the room from wall to wall, and over this the bronze tripod balanced. In my left hand I held a silver bowl of water gleaming like a mirror. In my right hand I clasped a laurel branch. The priestesses sang. Orisabios struck his gnarled staff upon the paving stones. Determinedly, he intoned the long remembered hymn to the Shining One, the Lord of Light and Inspiration, whose voice was in the wings of swans and the leaping of dolphins in the foam, and here beneath his temple in the prophetic vapours of the Earth.

Hail to you, Lord! Orisabios ended his incantations hoarsely, I seek your song, and I will sing thee another song too!

A silence filled the room. All eyes fell upon me, the child newly a woman perched on the bronze stool, not knowing now what I should do or say. For this part of the rite, there was no script like the play that preceded it.

‘Does Apollo speak to you yet, my child?’ The priest asked. He saw the answer in my frightened eyes. I felt no different than I had before. I breathed deeply, but I heard no hissing from the rocks, no sound beyond my heart beating in my ears.

After what seemed like a long time, our small party emerged into the temple above. The old women interpreted our silence and wept.

The priest told them, ‘Apollo has not yet returned to his temple.’

The first day, that seemed so magical, had spluttered to an ignominious end like all the abandoned fires of Greece.

I spent many nights in the year that followed huddled in the little room reserved for the Pythia. It had not been cleaned of the things left behind by my predecessor who had abandoned the world in despair and haste. Small clay pots of ointment indented with the impressions of her fingers, and glass jars of half-used perfumes, mysterious tinctures and potions littered the cedar wood benches. The large wooden throws and finely woven blankets smelled of alien creatures. On a carved timber stand facing the bed, the god’s bronze head, his skin shining smooth like silk, a dead dried laurel wreath upon his head, stared at me across the room and out of the centuries. The priests assigned a little girl younger than me to be my maid and companion, but all she did when she was in the room was sit in the corner and stare at me with large black eyes. When the sanctuary servants brought food, we ate together in silence. I heard them talking in whispers about me sometimes outside my room, but whenever I emerged, the people were quiet. I walked around the sanctuary like a ghost that people could not see. They did not know whether to curse me, the gods or their own misfortune. They only knew that the silence of the oracle had doomed them all to flounder, defenceless and unguided in the face of the new religion’s youthful zeal.

I had been trained in the songs and poetry of the gods. To me, they were like family. Every day as a child I had talked to them, especially bright Apollo, my divine father. I had never, until that first day in the sacred chamber, paused to hear the silence in return. While those around me despaired, I went to the temple library looking for answers. I buried myself in the scrolls, with the snores of old Pelias the librarian as my only company. The leak in the roof, the dust on the stairs, the echoes in the once busy chambers, reminded me every day of my mission to find the god - or, failing that, to know the truth. In the winter, I suffered the first agonies of doubt. Perhaps what the Christians said was true. I was a charlatan to be laughed at rather than revered. Such things were easy for ignorant city-dwellers to say, who lived in misery and squalor, illiterate and divorced from history and nature. Or so the cities had been described to me by Orisabios in his moments of anger when he still dared to look at me. What did I know of the world, I who had only words transcribed by men long dead to guide me.

Spring had come when the youth Antinous arrived at the sanctuary. I knew when the priestesses introduced him to me in the temple that he was supposed to be my lover.

One whispered to me, that ‘some have said there cannot be wisdom without love.’

I had marveled at the gleaming statue that stood in Hadrian’s treasury beside the temple, with its locks of hair like marble flames hung low around his brow and his neck, and the eyes that gazed down at me as if he were softer than the stone that bound him. I had no doubt that the young man had been chosen because of the likeness after the priestesses had spied my admiration. He was a dark deer-eyed boy with a face that was still smooth but his long locks of hair rested upon shoulders that were already broad and arms that looked strong enough to throw a javelin and wield a sword. His skin was not white like the marble, but bronzed by the sun. I admired the way the fine white cotton chiton had been fastened by tortoiseshell brooches at his neck, leaving his arms and shoulders bare.

‘Where are your sheep, boy?’ I asked.

He stared at me nervously and looked around him in amazement.

‘Where did you find him? Is he mute?’

‘He speaks. He is the son of Chiron, himself a shepherd.’

‘Leave us, and let us talk.’ I said.

The priests and priestesses scrambled away. I took young Antinous by the hand. He started at my touch as if he had touched a deamon.

‘Do you believe in the old miracles?’ I asked.

‘A man can never have enough gods to bless him. That is what my father says.’

‘It’s not what many people say these days. You know about the Christians?’

‘Of course I’ve heard of them. The folk in the cities worship their own god.’

‘They say he is our god too, that there is only one.’

‘I don’t know anything about that. I’m just a shepherd. I pray to Artemis every night. She keeps me safe in the night as well as the day.’

‘And she brought you here, to her brother’s temple.’

‘Tell me, are you real?’ He asked, ‘They say the god hasn’t spoken, that the gods are dead.’

‘So you have heard something!’ I said, ‘Who says these things?’

‘They talk in the village. Even the sanctuary guards whisper about it.’

‘You can tell me how real I am, later. Now, let’s go for a walk, away from the temple shadows. Our gods were always gods of nature, and these temples are their passing pavilions, not their true dwellings.’

‘Where will we go?’

‘We will take water from the Castallian spring. Perhaps there, the god will speak to you.’

He and I were both relieved. Neither of us were ready to go to my bedchamber. He followed me down the temple steps, and watched by a dozen pairs of eyes, we turned towards the mountain and made our way slowly across the amphitheatre of the Pheadriades. I heard his breathing relax behind me, and turned to see him smiling and sure-footed as a goat, at home on the mountain slope.

‘Did the priests dress you like that?’ I asked.

‘Yes. They said my sheepskin tunic was too dirty. The priestesses washed and combed my hair. Nobody ever did that besides my mother.’

‘Poor boy!’ I laughed, and I saw at once his resentment, ‘don’t think it is you I am laughing at. We are both characters in an unlikely play. Is Antinous even your real name?’

‘I like the name,’ was all he said.

‘Then I will call you by it.’

It was late in the morning when we reached the sacred glade of dappled light. We were both thirsty. I showed him where to cup his hands against the rock and collect the sweet water. I smiled again to see how eagerly he slaked his thirst and splashed water over his face. We sat beside the shallow creek beneath a twisted plane tree whose roots gripped around the rocks like long fingers reaching for the water.

‘What do you do all day, on the mountain slopes?’ I asked, ‘don’t you get lonely?’

‘I play the reed flute. When I tire of that, sometimes I sing.’ He said, ‘What do you do all day, in the temple?’

‘I read the scrolls.’

‘I cannot read.’

‘I could teach you.’

‘Do we have time for that?’

‘How soon do you expect to return to your flock?’

‘They ... they did not say.’

‘What did they tell you?’

‘That the Pythia is lonely in her sanctuary.’

‘You aren’t here to keep me company,’ I told him, ‘but to awake the god.’

‘How will we do that?’ He smiled at last.

‘Apollo loves music.’

‘I didn’t bring my aulos.’

‘But you can sing.’

‘I don’t sing for company.’

‘There is no one here, but me and the god.’

‘I will sing, if you tell me a story.’

I nodded. Antinous straightened his back and expanded his chest, and closing his eyes, he began to sing in a shepherd’s voice that was soothing but also full of joy. I took the chance to admire him shamelessly. His eyes opened and met my own in a moment of recognition, and I thought for an instant before I looked away, that we had met before.

***

When we returned to the sanctuary, the priestesses had lain out olive bread, honey and wine upon a table on the terrace in front of the amphitheater that overlooked the temple and the valley spread out below in its blossoming spring gown. They busied themselves as if it were a wedding feast, judging by our awkward glances and smiles whether or not they should celebrate or encourage us. Once we had satisfied our hunger, Antinous demanded the story in return for his love song. So I told him the story of Marsyas, the satyr who had picked up the aulos that the shepherd loved to play, after Athena had thrown it away because she had disliked how it puffed up her cheeks. Becoming such an expert at the instrument, Marsyas had challenged Apollo, the god of music, to a contest. The winner would be allowed to do whatever he pleased to the loser.

‘That seems foolish, given Apollo is the god of music.’ Antinous remarked.

‘Marsyas did not expect to win. But he thought that if he lost, Apollo might make love to him.’

Antinous laughed. ‘And did he?’

‘No, the god strung the foolish satyr up beneath a tree and skinned him alive.’

Antinous winced. ‘The gods can be cruel.’

‘Poor Marsyas bled so much, that the river that is named after him was formed in Asia.

‘Well, I never challenged Apollo to anything. You only asked me to sing for you!’

‘Don’t worry,’ I soothed him, ‘the story isn’t about the cruelty of the gods so much as the vanity of men.’

Antinous drank more wine. ‘I don’t like that story,’ he said. ‘And I don’t think one satyr could bleed so much.’

‘Do you think your song was better?’

‘Is this a trick?’ He asked, alarmed. ‘Why must the gods be always out to trick us into playing fools?’

‘I liked your song,’ I reassured him. ‘I had not heard it before. Where did you learn it?’

‘Apollo sent it to me in the water.’

‘That’s a good sign,’ I said, ‘but what do you know about love?’

‘Enough to sing about it.’

‘And only to sing?’

He blushed. And so did I.

‘You would rather make love to me than flay me, I hope,’ he blurted.

When we went at last to my bedchamber, I closed the door and lit the candles around Apollo’s head. Antinous watched me nervously as he sat upon the bed.

‘I am glad you know more about love than words,’ I told him, ‘because words are all I know.’

Gently, I unfastened his chiton and let it fall from his shoulders, revealing his barreled chest. The softness of it to touch surprised me. At first my fingers started back as if from a fire. ‘Don’t poke me,’ he asked, ‘but kiss me, like this.’

That night, I dreamed of the mountain. Like a bird, I flew from from the temple steps towards the slopes, glowing like roses in the dawn. I soared above its crown, seeing things I could never have seen. I saw Antinous playing his aulos among white sheep, who floated like clouds around him. I called to him, but he did not answer. I looked north and saw dark clouds gathering like winter, then rushing towards us, full of lightening. I turned to tell Antinous to run, but he was gone. I was tethered to the mountain, and the mountain would not let me go. I woke drenched in sweat. The shepherd’s naked body was still beside me, as still as the statue, but as hot as hearth flames. I reveled in the fact that he was real, and not a dream. I knew that he must leave me, and that night only longed to follow him.

***

The following night, the earth trembled. I woke to a rumbling from deep under the mountain. Antinous pulled at me, saying we should hide under the bed. I gripped him in return, but stayed where I was. Nobody came to the small chamber I had made my home. They were still cowering in fear when I ran up the sacred way, lit only by blue light of the stars. Antinous followed me, half out of fear. The arms of the mountain gleamed dimly in the moonlight and overhead the heaven was aglow with constellations. Bright Aphrodite’s star was perched over the crown of the Mountain – an auspicious sign.

Old Orisabios met me in the temple Adyton, between the colonnades and the inner hall. He counted more cracks in the temple face, but concluded that we were still safe.

‘Poseidon’s horses have had mercy upon us!’ He said.

‘Take me to the Cellar.’ I said. ‘But first, beat the gong to summon the priestesses. Bring me laurel leaves and the holy water.’

I knew something had changed that night, despite the protestations of the priestesses and my priest that the ritual fasting and cleansing had not been observed. I could smell the sweet scent of the god filling the chamber as I gripped the silver bowl and laurel branch. I heard the hissing sound from the crack in the earth, and behind me the torch flame was flaring in the exhalations of the earth. Antinous watched, doe-eyed and delirious, as the priestesses sang and the old man wept with joy.

The night the god spoke to me I became Pythia. For it was not the god’s voice I heard first, but the cries of my predecessors. A thousand years of prophecies danced before my eyes. I had learned the most famous pronouncements, but now these episodes of history appeared to me as though I were living them, as if the memories of a millennia welled up out of the earth that had witnessed them and poured themselves into me with each ecstatic inhalation.

At first I was the burning breath of the mountain itself. The trembling earth hissed as it expelled me from its molten heart. Heat cracking rock. Shocks of cold air. Shot out of darkness into midday sun. Then I had hooved feet, scrabbling on rocky ground, seeking tender shoots and buds between the mountain’s shining arms. Ecstatic clover! Brilliant sun! Beautiful rocks! I was the mind of god trapped within a goat’s body, flailing wildly over the cracks of earth.

I saw a young man’s face, laughing. Then I felt his fear as I seized him too. Soaring vision. The wide view of the valley from the mountainside, dark green and shimmering in the haze of summer - a thing new and delightful to me though I knew it well. I recognised my home, the valley barely changed in a thousand years. This was my first human host - the young goatsherd. God within the body of a man.

Then I saw bare breasted Cretan women and smiling men in blue loincloths, telling me of their journeys across the waves, in the escort of dolphins and the shining sun, rolling across waves in search of - Me! These were my first priests and priestesses. The first Pythia, a young woman, soon came to me, afraid and full of wonder as I had been that first day.

Among the multitudes of pilgrims, faces flashed by of the glorious as well as the meek. Lycurgus, Pericles, Phillip of Macedon, Alexander - the faces of men appeared to me as if I could still touch their necks, as if these heroes still lived a heartbeat away from my own. And between these generations I passed through the generations of myself - I, Pythia! How many deaths I suffered and witnessed in those moments – until the door of life held no more fear for me. But then a new fear rose in me – that I should be the last of my kind. In the procession of seers, at the last I saw my predecessor look out across the valley from the mountain top. I felt her despair and grief and guilt. When the Emperor Julian’s emissary came seeking to restore the gods of Greece, desperate for signs of hope, the god was silent and I had offered nothing but pity and despair. When Julian fell to the assassin’s blade, only philosophers wept. And I, Pythia. I saw myself falling from the mountain, the jagged limestone rushing up to meet me. When I opened my eyes I was in the arms of my father and the priestesses, wide eyed and euphoric. I had also seen the future, at last, and with it, I foresaw my fate.

The tremor had woken the mountain’s fire, but instead of pilgrims, it was the Christians who came, emissaries of a new hostile monarch. The mountain had trembled too late, indifferent to the demands of mortal kings.

***

The emissary from the upstart city they now called Constantinople was a young man named Justin. His eyes smoldered fervently. He wore a long black tunic in the new style down to his calves, and boots instead of sandals, a practical symbol of the cold seasons ushered in by the Christian’s austere god. He brandished a parchment containing the order ‘that all pagan worship should cease, and particularly, that the sanctuary of Apollo at Delphi should be closed.’

He told us, ‘Seek forgiveness for your errors and be baptised in the name of the Lord our God, Jesus Christ. This much, I can arrange for you.’ There was threat as much as entreaty in his voice.

One of the priestesses stifled a sob. There had been whispered hopes at the appearance of the emissary that perhaps the Christian god would take possession of the sanctuary as Apollo had done from Python. That he would destroy it entirely was beyond their comprehension.

Antinous interjected fearlessly, ‘The rite is real, and so is the god’s voice. I have heard it myself!’

It had been many days since Antinous had come to the sanctuary. In the excitement of my prophecies, I told the priest that he was a valuable witness as well as a source of inspiration to the god. The truth was that we were in the midst of youthful passion. Love had saved me for the world when I was near despair. Now it strengthened my resolve.

‘Yes,’ Orisabios insisted, ‘Tell the Emperor that Apollo’s prophetic air flows once more. Tell him to come and see for himself. If you want proof, we will consult the god now.’

Justin scowled, ‘We have no use for your idols and witchcraft, old man.’

I looked at him, ‘Are you not curious to see this rite that you would have us end?’

‘Idolatry has been forbidden. It is against the God’s Commandment.’

‘And yet the Christians venerate images of their Jesus and Mary. How is that different to the statues of Apollo and his mother, Leto? Both of the haloed gods came out of the east.’

Justin was dismissive, ‘It is a different thing. Your god is one of many, a lie. There is only one God, Jesus his son …’

‘Apollo is the son of Zeus.’

‘… and Mary his virgin mother …’

‘Leto was a virgin too, until the God entered her.’

‘ … who bore him of the Holy Spirit …’

‘Who are you to say it is a different spirit to the one that resides here?’

‘There is only one God!’

‘And yet, already, in your speech he has assumed many faces. A father, a son, a mother, a spirit.’

‘You can take your argument to the emperor, if you can get past his people.’

‘And so we come to the truth of it. It is the emperor’s will, not God’s. Yet it is true,’ I said, ‘that the god whom Julian sought in vain has spoken to me.’

‘We curse the name of the apostate emperor Julian,’ Justin spat. ‘His reign was a reminder from God that we have unfinished business. Never again will an emperor come here, where the pagan devils rule. You speak of the cracks of Hell, but our Lord speaks of the Kingdom of Heaven. God is not of this world. Down there,’ Justin pointed at the earth, ‘There is the realm of evil, the earth from which you conjour your own voices of doom. God’s kingdom is eternal.’

‘I have had a dream,’ I said to my priests as well as to the hostile emissary, ‘that the mountain does not move. But I will. I will go to the emperor myself and appeal to him. If he will not listen to my appeal, then we will close the sanctuary.’ I turned to Justin, ‘My priests tell me that you have a mob outside our gates. Don’t think that we won’t defend the holy places. Wouldn’t it be better to do so without bloodshed? And what better trophy to bring to your emperor than the oracle of Delphi? I will even bring the bronze tripod to set in the Hippodrome of Constantinople with my own hands as a sign of your god’s victory.’

The Christian worried at his crucifix with his fingers. He had not thought of trophies or of captives, but he was not at all beyond thoughts of worldly glory. I saw in his mind, the thought of returning to the New Rome as if he were a conquering general rather than a mere messenger. At the same time he looked around him, at the guards we had dressed in their finest gear and golden helms to hide their age and weariness.

‘You will close the sanctuary to pilgrims in the meantime, but your people may keep possession of it while they await the emperor’s will.’

***

In the evening, Orisabios and the priestesses were one voice in warning me against the mission I had chosen. But none of them would stop me when they had no other hope.

‘It will buy us time,’ the chief priest said at last, ‘and time has seen off many a king when arms and argument have failed.’

‘I will walk slowly then.’ I smiled.

‘I will come with you.’

‘No. I know you are my father. But you do not need to come on a journey that the god has given me alone.’

He looked at me with wide eyes. ‘Who told you?’

‘Don’t you believe that the god spoke to me? He showed me with his own eyes, the moment when you went to my mother with the god’s mask on your face.’

My father drew back. He had so long believed the gods were dead, that now he could not believe they lived.

‘So it is true? There is hope?’

‘My dream has not shown me hope.’ I said, ‘Only fate.’

‘Still, you cannot go alone.’

‘I will take one guard. I must go quietly, without fanfare. If it is known too widely that I am coming, and why, the Christians will stop us. It is well-known that they have many factions that outdo each other in violence.’

‘I will pick your escort myself.’

‘Only if you intend to pick Antinous.’

***

I left the sanctuary in the company of men who each believed in their own mission. Justin, with his small band of Christians, believed he was on the brink of god’s glory. Antinous, as my escort, believed as fervently in our quest as he did in me. All of them were like sheep, and I, Pythia, the silent shepherd, had my own path laid out before me, on the crossroads between life and what could only end in a miracle or martyrdom.

The Christians did not interrogate my silence on the road, believing it to be one of despair or delusion. Antinous, seeing my lips move and my eyes stare ahead of me, believed I was still possessed by Apollo. The truth was that I did not wish to give away my thoughts to him too soon.

We camped at the end of the daylong trek down the pass at Thermopylae, not far from the first slopes of Mount Olympus. We had hoped to reach the town of Dion before the dusk, but I pleaded that my horse had injured its foot on the mountain paths. We sat, as was our way, a little apart from the Christians. Justin always sat closest to us, watching his trophies.

‘Are you ready to die, my love?’ I whispered.

‘Don’t talk like that.’ He said, ‘when you speak with the voice of the god, the emperor will see the error of his ways.’

I told him then, that the god’s voice did not leave the mountain.

‘Besides,’ I said softly, ‘you don’t know what a fool I would look on my bronze tripod, before the emperor on his porphyry throne in the Golden Hall of the Great Palace of Constantinople.’

Antinous shook his head, ‘He will listen to your arguments then. Didn’t the god speak to you and show you the future in the temple cellar? You gave us hope!’

‘Hope! That was the final curse to escape from Pandora’s jar,’ I said.

I told him that with perfect clarity I had foreseen all our fates, and the red and blue colours of hope and fear that led us there. It was not hope but defiance that led me to the emperor’s court.

‘What will you do,’ I asked, ‘if the mob finds me at the emperor’s door and stones me to death in the square?’

‘I will not let anyone hurt you!’ Antinous told me.

‘Are you really so ready to die for me?’ I asked.

‘Is this really our fate?’ In his eyes, I saw more sadness than fear.

He wondered at last, ‘Will you renounce Apollo, then, and become a Christian?’

I shook my head, ‘The Pythia could never live the life of lies.’

‘Then neither will I.’ He announced.

‘How eager men are to die,’ I whispered, ‘when we might still live.’

Loudly, I asked him to find us rabbits – for the Christians were all hungry.

Happily, the Christians shared our food. Justin alone refused.

When everyone was sleeping, I woke Antinous and motioned him to follow me in the starlight.

‘Where are we going?’ Antinous asked. So eager was he to follow me, that he did not argue.

‘Into life, my love.’

‘What about our horses?’ He whispered.

‘We will not need them on the mountain.’

‘But the Christians will follow us.’

‘They will not wake for days,’ I told him, ‘from the potion I put in their rabbit.’

‘But Justin …’

‘Let him follow us alone, if he wants his prize.’

We took only the supplies that we could carry over our shoulders. I grasped the bronze tripod in my hands. Justin was soon awake as the horses startled at our departure, but as I knew he would, he wasted time in trying to rouse his men with cries and shaking. The noise of breaking bushes and curses followed soon after, and we ran through the trees as fast as we dared in the perilous darkness.

Then the moon came from behind a cloud and lit our path. I knew our white chitons gleamed in the night, that Justin would look up and see us as we began to climb the mountain’s feet, heading for the canyon by the sound of its sacred stream and waterfalls.

‘We are not going to Byzantium?’ Antinous asked. ‘What of the mission from Apollo?’

‘Apollo did not give me a mission.’ I told him, ‘I only said so to ease our escape from my own followers. Now we must evade another god’s follower, one more time.’

Antinous paused, ‘Then there is no hope?’

‘Hope is not the gift of the oracle.’ I told him, ‘Knowledge is its gift. Know that men have only two paths, to live in love or in hate, and at the end some are fortunate enough to choose whether to die in violence or in peace.’

As Antinous considered these words from lips he had trusted so blindly until now, I stopped in the glade of ancient plane trees that stand in the shadowy grotto between the mountain’s toes. Blue moonlight pooled upon the rustling earth. The sound of water racing coldly over stones beyond the thicket grew louder as we listened. I heard my heart racing too, and Antinous breathing. Julian’s boots beat towards us. Loudly, I sang a prayer to the nymphs of the water and the driads who lived in the trees.

‘What are we doing?’ Antinous whispered urgently.

‘We are waking the sleeping spirits, and asking for their protection.’

‘Will they help us,’ Antinous asked, ‘when we have fled from our quest?’

‘We are not fleeing. We are coming home.’

As if in answer, a wind from the east whispered through the tree tops.

‘You are the sure-footed shepherd,’ I told Antinous at last, ‘find us a way up the mountain, and I will follow.’

He looked at me, in my white chiton, still grasping the god’s bronze stool with both my hands.

‘You cannot climb with that. If you bring the tripod, you will fall.’ He warned.

Now I hesitated, though I knew what he said was true.

‘We are running or making a stand, we cannot do both.’ He pointed out.

For a moment, I thought of the Temple I had abandoned. I imagined Christians rampaging through its treasury, the gold melted down, the marble faces broken in the dust. ‘I must save something.’

‘Haven’t you already saved me?’

For a moment I considered flinging the tripod into the river, but I could not farewell the holy things with anything but dignity in the end. So I left the tripod in the middle of the glade, knowing that Justin would find it there, alone and ringed by the whispering planes.

‘We must hurry!’ Antinous called me.

As we climbed the mountain where we would live out our days among the forests, caves and waterfalls, we heard screams behind us. They were of a man, crying like a boy, frightened in the dark.

‘What is that?’ Antinous asked.

‘Justin has found the tripod.’ I said.

‘Then he will not be far behind us!’

‘No,’ I told him, as Antinous listened with wide eyes to the terrified screams below us, ‘Justin will not climb the mountain, not tonight.’

I had put a different potion in his drinking water – an elixir of the earth that showed a man his deepest fears, and drawn to its magic scent, the spirits of the living glade had found him.

© AK Paul

August 2017.