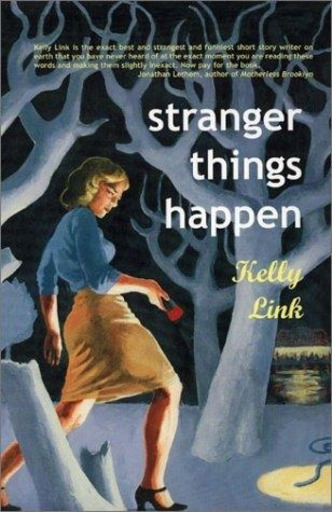

Stranger Things Happen

Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.5

You are free:

- to copy, distribute, display, and perform the work

- to make derivative works

Under the following conditions:

Attribution. You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author or licensor.

Noncommercial. You may not use this work for commercial purposes.

Share Alike. If you alter, transform, or build upon this work, you may distribute the resulting work only under a license identical to this one.

- For any reuse or distribution, you must make clear to others the license terms of this work.

- Any of these conditions can be waived if you get permission from the copyright holder.

Dear Mary (if that is your name),

I bet you'll be pretty surprised to hear from me. It really is me, by the way, although I have to confess at the moment that not only can I not seem to keep your name straight in my head, Laura? Susie? Odile? but I seem to have forgotten my own name. I plan to keep trying different combinations: Joe loves Lola, Willy loves Suki, Henry loves you, sweetie, Georgia?, honeypie, darling. Do any of these seem right to you?

All last week I felt like something was going to happen, a sort of bees and ants feeling. Something was going to happen. I taught my classes and came home and went to bed, all week waiting for the thing that was going to happen, and then on Friday I died.

One of the things I seem to have misplaced is how, or maybe I mean why. It's like the names. I know that we lived together in a house on a hill in a small comfortable city for nine years, that we didn't have kids—except once, almost—and that you're a terrible cook, oh my darling, Coraline? Coralee? and so was I, and we ate out whenever we could afford to. I taught at a good university, Princeton? Berkeley? Notre Dame? I was a good teacher, and my students liked me. But I can't remember the name of the street we lived on, or the author of the last book I read, or your last name which was also my name, or how I died. It's funny, Sarah? but the only two names I know for sure are real are Looly Bellows, the girl who beat me up in fourth grade, and your cat's name. I'm not going to put your cat's name down on paper just yet.

We were going to name the baby Beatrice. I just remembered that. We were going to name her after your aunt, the one that doesn't like me. Didn't like me. Did she come to the funeral?

I've been here for three days, and I'm trying to pretend that it's just a vacation, like when we went to that island in that country. Santorini? Great Britain? The one with all the cliffs. The one with the hotel with the bunkbeds, and little squares of pink toilet paper, like handkerchiefs. It had seashells in the window too, didn't it, that were transparent like bottle glass? They smelled like bleach? It was a very nice island. No trees. You said that when you died, you hoped heaven would be an island like that. And now I'm dead, and here I am.

This is an island too, I think. There is a beach, and down on the beach is a mailbox where I am going to post this letter. Other than the beach, the mailbox, there is the building in which I sit and write this letter. It seems to be a perfectly pleasant resort hotel with no other guests, no receptionist, no host, no events coordinator, no bell-boy. Just me. There is a television set, very old-fashioned, in the hotel lobby. I fiddled the antenna for a long time, but never got a picture. Just static. I tried to make images, people out of the static. It looked like they were waving at me.

My room is on the second floor. It has a sea view. All the rooms here have views of the sea. There is a desk in my room, and a good supply of plain, waxy white paper and envelopes in one of the drawers. Laurel? Maria? Gertrude?

I haven't gone out of sight of the hotel yet, Lucille? because I am afraid that it might not be there when I get back.

Yours truly, You know who.

#

The dead man lies on his back on the hotel bed, his hands busy and curious, stroking his body up and down as if it didn't really belong to him at all. One hand cups his testicles, the other tugs hard at his erect penis. His heels push against the mattress and his eyes are open, and his mouth. He is trying to say someone's name.

Outside, the sky seems much too close, made out of some grey stuff that only grudgingly allows light through. The dead man has noticed that it never gets any lighter or darker, but sometimes the air begins to feel heavier, and then stuff falls out of the sky, fist-sized lumps of whitish-grey doughy matter. It falls until the beach is covered, and immediately begins to dissolve. The dead man was outside, the first time the sky fell. Now he waits inside until the beach is clear again. Sometimes he watches television, although the reception is poor.

The sea goes up and back the beach, sucking and curling around the mailbox at high tide. There is something about it that the dead man doesn't like much. It doesn't smell like salt the way a sea should. Cara? Jasmine? It smells like wet upholstery, burnt fur.

#

Dear May? April? Ianthe?

My room has a bed with thin, limp sheets and an amateurish painting

of a woman sitting under a tree. She has nice breasts, but a

peculiar expression on her face, for a woman in a painting in a

hotel room, even in a hotel like this. She looks disgruntled.

I have a bathroom with hot and cold running water, towels, and a mirror. I looked in the mirror for a long time, but I didn't look familiar. It's the first time I've ever had a good look at a dead person. I have brown hair, receding at the temples, brown eyes, and good teeth, white, even, and not too large. I have a small mark on my shoulder, Celeste? where you bit me when we were making love that last time. Did you somehow realize it would be the last time we made love? Your expression was sad; also, I seem to recall, angry. I remember your expression now, Eliza? You glared up at me without blinking and when you came, you said my name, and although I can't remember my name, I remember you said it as if you hated me. We hadn't made love for a long time.

I estimate my height to be about five feet, eleven inches, and although I am not unhandsome, I have an anxious, somewhat fixed expression. This may be due to circumstances.

I was wondering if my name was by any chance Roger or Timothy or Charles. When we went on vacation, I remember there was a similar confusion about names, although not ours. We were trying to think of one for her, I mean, for Beatrice. Petrucchia, Solange? We wrote them all with long pieces of stick on the beach, to see how they looked. We started with the plain names, like Jane and Susan and Laura. We tried practical names like Polly and Meredith and Hope, and then we became extravagant. We dragged our sticks through the sand and produced entire families of scowling little girls named Gudrun, Jezebel, Jerusalem, Zedeenya, Zerilla. How about Looly, I said. I knew a girl named Looly Bellows once. Your hair was all snarled around your face, stiff with salt. You had about a zillion freckles. You were laughing so hard you had to prop yourself up with your stick. You said that sounded like a made-up name.

Love,

You know who.

#

The dead man is trying to act as if he is really here, in this place. He is trying to act in a normal and appropriate fashion. As much as is possible. He is trying to be a good tourist.

He hasn't been able to fall asleep in the bed, although he has turned the painting to the wall. He is not sure that the bed is a bed. When his eyes are closed, it doesn't seem to be a bed. He sleeps on the floor, which seems more floorlike than the bed seems bedlike. He lies on the floor with nothing over him and pretends that he isn't dead. He pretends that he is in bed with his wife and dreaming. He makes up a nice dream about a party where he has forgotten everyone's name. He touches himself. Then he gets up and sees that the white stuff that has fallen out of the sky is dissolving on the beach, little clumps of it heaped around the mailbox like foam.

#

Dear Elspeth? Deborah? Frederica?

Things are getting worse. I know that if I could just get your name

straight, things would get better.

I told you that I'm on an island, but I'm not sure that I am. I'm having doubts about my bed and the hotel. I'm not happy about the sea or the sky, either. The things that have names that I'm sure of, I'm not sure they're those things, if you understand what I'm saying, Mallory? I'm not sure I'm still breathing, either. When I think about it, I do.

I only think about it because it's too quiet when I'm not. Did you know, Alison? that up in those mountains, the Berkshires? the altitude gets too high, and then real people, live people forget to breathe also? There's a name for when they forget. I forget what the name is.

But if the bed isn't a bed, and the beach isn't a beach, then what are they? When I look at the horizon, there almost seem to be corners. When I lay down, the corners on the bed receded like the horizon.

Then there is the problem about the mail. Yesterday I simply slipped the letter into a plain envelope, and slipped the envelope, unaddressed, into the mailbox. This morning the letter was gone and when I stuck my hand inside, and then my arm, the sides of the box were damp and sticky. I inspected the back side and discovered an open panel. When the tide rises, the mail goes out to sea. So I really have no idea if you, Pamela? or, for that matter, if anyone is reading this letter.

I tried dragging the mailbox further up the beach. The waves hissed and spit at me, a wave ran across my foot, cold and furry and black, and I gave up. So I will simply have to trust to the local mail system.

Hoping you get this soon,

You know who.

#

The dead man goes for a walk along the beach. The sea keeps its distance, but the hotel stays close behind him. He notices that the tide retreats when he walks towards it, which is good. He doesn't want to get his shoes wet. If he walked out to sea, would it part for him like that guy in the bible? Onan?

He is wearing his second-best suit, the one he wore for interviews and weddings. He figures it's either the suit that he died in, or else the one that his wife buried him in. He has been wearing it ever since he woke up and found himself on the island, disheveled and sweating, his clothing wrinkled as if he had been wearing it for a long time. He takes his suit and his shoes off only when he is in his hotel room. He puts them back on to go outside. He goes for a walk along the beach. His fly is undone.

The little waves slap at the dead man. He can see teeth under that water, in the glassy black walls of the larger waves, the waves farther out to sea. He walks a fair distance, stopping frequently to rest. He tires easily. He keeps to the dunes. His shoulders are hunched, his head down. When the sky begins to change, he turns around. The hotel is right behind him. He doesn't seem at all surprised to see it there. All the time he has been walking, he has had the feeling that just over the next dune someone is waiting for him. He hopes that maybe it is his wife, but on the other hand if it were his wife, she'd be dead too, and if she were dead, he could remember her name.

#

Dear Matilda? Ivy? Alicia?

I picture my letters sailing out to you, over those waves with the

teeth, little white boats. Dear reader, Beryl? Fern? you would like

to know how I am so sure these letters are getting to you? I

remember that it always used to annoy you, the way I took things

for granted. But I'm sure you're reading this in the same way that

even though I'm still walking around and breathing (when I remember

to) I'm sure I'm dead. I think that these letters are getting to

you, mangled, sodden but still legible. If they arrived the regular

way, you probably wouldn't believe they were from me, anyway.

I remembered a name today, Elvis Presley. He was the singer, right? Blue shoes, kissy fat lips, slickery voice? Dead, right? Like me. Marilyn Monroe too, white dress blowing up like a sail, Gandhi, Abraham Lincoln, Looly Bellows (remember?) who lived next door to me when we were both eleven. She had migraine headaches all through the school year, which made her mean. Nobody liked her, before, when we didn't know she was sick. We didn't like her after. She broke my nose because I pulled her wig off one day on a dare. They took a tumor out of her head that was the size of a chicken egg but she died anyway.

When I pulled her wig off, she didn't cry. She had brittle bits of hair tufting out of her scalp and her face was swollen with fluid like she'd been stung by bees. She looked so old. She told me that when she was dead she'd come back and haunt me, and after she died, I pretended that I could see not just her—but whole clusters of fat, pale, hairless ghosts lingering behind trees, swollen and humming like hives. It was a scary fun game I played with my friends. We called the ghosts loolies, and we made up rules that kept us safe from them. A certain kind of walk, a diet of white food—marshmallows, white bread rolled into pellets, and plain white rice. When we got tired of the loolies, we killed them off by decorating her grave with the remains of the powdered donuts and Wonderbread our suspicious mothers at last refused to buy for us.

Are you decorating my grave, Felicity? Gay? Have you forgotten me yet? Have you gotten another cat yet, another lover? or are you still in mourning for me? God, I want you so much, Carnation, Lily? Lily? Rose? It's the reverse of necrophilia, I suppose—the dead man who wants one last fuck with his wife. But you're not here, and if you were here, would you go to bed with me?

I write you letters with my right hand, and I do the other thing with my left hand that I used to do with my left hand, ever since I was fourteen, when I didn't have anything better to do. I seem to recall that when I was fourteen there wasn't anything better to do. I think about you, I think about touching you, think that you're touching me, and I see you naked, and you're glaring at me, and I'm about to shout out your name, and then I come and the name on my lips is the name of some dead person, or some totally made-up name.

Does it bother you, Linda? Donna? Penthesilia? Do you want to know the worst thing? Just a minute ago I was grinding into the pillow, bucking and pushing and pretending it was you, Stacy? under me, oh fuck it felt good, just like when I was alive and when I came I said, "Beatrice." And I remembered coming to get you in the hospital after the miscarriage.

There were a lot of things I wanted to say. I mean, neither of us was really sure that we wanted a baby and part of me, sure, was relieved that I wasn't going to have to learn how to be a father just yet, but there were still things that I wish I'd said to you. There were a lot of things I wish I'd said to you.

You know who.

#

The dead man sets out across the interior of the island. At some point after his first expedition, the hotel moved quietly back to its original location, the dead man in his room, looking into the mirror, expression intent, hips tilted against the cool tile. This flesh is dead. It should not rise. It rises. Now the hotel is back beside the mailbox, which is empty when he walks down to check it.

The middle of the island is rocky, barren. There are no trees here, the dead man realizes, feeling relieved. He walks for a short distance—less than two miles, he calculates, before he stands on the opposite shore. In front of him is a flat expanse of water, sky folded down over the horizon. When the dead man turns around, he can see his hotel, looking forlorn and abandoned. But when he squints, the shadows on the back veranda waver, becoming a crowd of people, all looking back at him. He has his hands inside his pants, he is touching himself. He takes his hands out of his pants. He turns his back on the shadowy porch.

He walks along the shore. He ducks down behind a sand dune, and then down a long hill. He is going to circle back. He is going to sneak up on the hotel if he can, although it is hard to sneak up on something that always seems to be trying to sneak up on you. He walks for a while, and what he finds is a ring of glassy stones, far up on the beach, driftwood piled inside the ring, charred and black. The ground is trampled all around the fire, as if people have stood there, waiting and pacing. There is something left in tatters and skin on a spit in the center of the campfire, about the size of a cat. The dead man doesn't look too closely at it.

He walks around the fire. He sees tracks indicating where the people who stood here, watching a cat roast, went away again. It would be hard to miss the direction they are taking. The people leave together, rushing untidily up the dune, barefoot and heavy, the imprints of the balls of the foot deep, heels hardly touching the sand at all. They are headed back towards the hotel. He follows the footprints, sees the single track of his own footprints, coming down to the fire. Above, in a line parallel to his expedition and to the sea, the crowd has walked this way, although he did not see them. They are walking more carefully now, he pictures them walking more quietly.

His footprints end. There is the mailbox, and this is where he left the hotel. The hotel itself has left no mark. The other footprints continue towards the hotel, where it stands now, small in the distance. When the dead man gets back to the hotel, the lobby floor is dusted with sand, and the television is on. The reception is slightly improved. But no one is there, although he searches every room. When he stands on the back veranda, staring out over the interior of the island, he imagines he sees a group of people, down beside the far shore, waving at him. The sky begins to fall.

#

Dear Araminta? Kiki? Lolita?

Still doesn't have the right ring to it, does it? Sukie? Ludmilla?

Winifred?

I had that same not-dream about the faculty party again. She was there, only this time you were the one who recognized her, and I was trying to guess her name, who she was. Was she the tall blonde with the nice ass, or the short blonde with the short hair who kept her mouth a little open, like she was smiling all the time? That one looked like she knew something I wanted to know, but so did you. Isn't that funny? I never told you who she was, and now I can't remember. You probably knew the whole time anyway, even if you didn't think you did. I'm pretty sure you asked me about that little blond girl, when you were asking.

I keep thinking about the way you looked, that first night we slept together. I'd kissed you properly on the doorstep of your mother's house, and then, before you went inside, you turned around and looked at me. No one had ever looked at me like that. You didn't need to say anything at all. I waited until your mother turned off all the lights downstairs, and then I climbed over the fence, and up the tree in your backyard, and into your window. You were leaning out of the window, watching me climb, and you took off your shirt so that I could see your breasts, I almost fell out of the tree, and then you took off your jeans and your underwear had a day of the week embroidered on it, Holiday? and then you took off your underwear too. You'd bleached the hair on your head yellow, and then streaked it with red, but the hair on your pubis was black and soft when I touched it.

We lay down on your bed, and when I was inside you, you gave me that look again. It wasn't a frown, but it was almost a frown, as if you had expected something different, or else you were trying to get something just right. And then you smiled and sighed and twisted under me. You lifted up smoothly and strongly as if you were going to levitate right off the bed, and I lifted with you as if you were carrying me and I almost got you pregnant for the first time. We never were good about birth control, were we, Eliane? Rosemary? And then I heard your mother out in the backyard, right under the elm I'd just climbed, yelling "Tree? Tree?"

I thought she must have seen me climb it. I looked out the window and saw her directly beneath me, and she had her hands on her hips, and the first thing I noticed were her breasts, moonlit and plump, pushed up under her dressing gown, fuller than yours and almost as nice. That was pretty strange, realizing that I was the kind of guy who could have fallen in love with someone after not so much time, really, truly, deeply in love, the forever kind, I already knew, and still notice this middle-aged woman's tits. Your mother's tits. That was the second thing I learned. The third thing was that she wasn't looking back at me. "Tree?" she yelled one last time, sounding pretty pissed.

So, okay, I thought she was crazy. The last thing, the thing I didn't learn, was about names. It's taken me a while to figure that out. I'm still not sure what I didn't learn, Aina? Jewel? Kathleen? but at least I'm willing. I mean, I'm here still, aren't I?

Wish you were here, You know who.

#

At some point, later, the dead man goes down to the mailbox. The water is particularly unwaterlike today. It has a velvety nap to it, like hair. It raises up in almost discernable shapes. It is still afraid of him, but it hates him, hates him, hates him. It never liked him, never. "Fraidy cat, fraidy cat," the dead man taunts the water.

When he goes back to the hotel, the loolies are there. They are watching television in the lobby. They are a lot bigger than he remembers.

#

Dear Cindy, Cynthia, Cenfenilla,

There are some people here with me now. I'm not sure if I'm in

their place— if this place is theirs, or if I brought them here,

like luggage. Maybe it's some of one, some of the other. They're

people, or maybe I should say a person I used to know when I was

little. I think they've been watching me for a while, but they're

shy. They don't talk much.

Hard to introduce yourself, when you have forgotten your name. When I saw them, I was astounded. I sat down on the floor of the lobby. My legs were like water. A wave of emotion came over me, so strong I didn't recognize it. It might have been grief. It might have been relief. I think it was recognition. They came and stood around me, looking down. "I know you," I said. "You're loolies."

They nodded. Some of them smiled. They are so pale, so fat! When they smile, their eyes disappear in folds of flesh. But they have tiny soft bare feet, like children's feet. "You're the dead man," one said. It had a tiny soft voice. Then we talked. Half of what they said made no sense at all. They don't know how I got here. They don't remember Looly Bellows. They don't remember dying. They were afraid of me at first, but also curious.

They wanted to know my name. Since I didn't have one, they tried to find a name that fit me. Walter was put forward, then rejected. I was un-Walter-like. Samuel, also Milo, also Rupert. Quite a few of them liked Alphonse, but I felt no particular leaning towards Alphonse. "Tree," one of the loolies said.

Tree never liked me very much. I remember your mother standing under the green leaves that leaned down on bowed branches, dragging the ground like skirts. Oh, it was such a tree! the most beautiful tree I'd ever seen. Halfway up the tree, glaring up at me, was a fat black cat with long white whiskers, and an elegant sheeny bib. You pulled me away. You'd put a T-shirt on. You stood in the window. "I'll get him," you said to the woman beneath the tree. "You go back to bed, mom. Come here, Tree."

Tree walked the branch to the window, the same broad branch that had lifted me up to you. You, Ariadne? Thomasina? plucked him off the sill and then closed the window. When you put him down on the bed, he curled up at the foot, purring. But when I woke up, later, dreaming that I was drowning, he was crouched on my face, his belly heavy as silk against my mouth.

I always thought Tree was a silly name for a cat. When he got old and slept out in the garden, he still didn't look like a tree. He looked like a cat. He ran out in front of my car, I saw him, you saw me see him, I realized that it would be the last straw—a miscarriage, your husband sleeps with a graduate student, then he runs over your cat—I was trying to swerve, to not hit him. Something tells me I hit him. I didn't mean to, sweetheart, love, Pearl? Patsy? Portia?

You know who.

#

The dead man watches television with the loolies. Soap operas. The loolies know how to get the antenna crooked so that the reception is decent, although the sound does not come in. One of them stands beside the TV to hold it just so. The soap opera is strangely dated, the clothes old-fashioned, the sort the dead man imagines his grandparents wore. The women wear cloche hats, their eyes are heavily made up.

There is a wedding. There is a funeral, also, although it is not clear to the dead man watching, who the dead man is. Then the characters are walking along a beach. The woman wears a black-and-white striped bathing costume that covers her modestly, from neck to mid-thigh. The man's fly is undone. They do not hold hands. There is a buzz of comment from the loolies. "Too dark," one says, about the woman. "Still alive," another says.

"Too thin," one says, indicating the man. "Should eat more. Might blow away in a wind."

"Out to sea."

"Out to Tree." The loolies look at the dead man. The dead man goes to his room. He locks the door. His penis sticks up, hard as a tree. It is pulling him across the room, towards the bed. The man is dead, but his body doesn't know it yet. His body still thinks that it is alive. He begins to say out loud the names he knows, beautiful names, silly names, improbable names. The loolies creep down the hall. They stand outside his door and listen to the list of names.

#

Dear Bobbie? Billie?

I wish you would write back.

You know who.

#

When the sky changes, the loolies go outside. The dead man watches them pick the stuff off the beach. They eat it methodically, chewing it down to a paste. They swallow, and pick up more. The dead man goes outside. He picks up some of the stuff. Angel food cake? Manna? He smells it. It smells like flowers: like carnations, lilies, like lilies, like roses. He puts some in his mouth. It tastes like nothing at all. The dead man kicks at the mailbox.

#

Dear Daphne? Proserpine? Rapunzel?

Isn't there a fairy tale where a little man tries to do this? Guess

a woman's name? I have been making stories up about my death. One

death I've imagined is when I am walking down to the subway, and

then there is a strong wind, and the mobile sculpture by the

subway, the one that spins in the wind, lifts up and falls on me.

Another death is you and I, we are flying to some other country,

Canada? The flight is crowded, and you sit one row ahead of me.

There is a crack! and the plane splits in half, like a cracked

straw. Your half rises up and my half falls down. You turn and look

back at me, I throw out my arms. Wineglasses and newspapers and

ribbons of clothes fall up in the air. The sky catches fire. I

think maybe I stepped in front of a train. I was riding a bike, and

someone opened a car door. I was on a boat and it sank.

This is what I know. I was going somewhere. This is the story that seems the best to me. We made love, you and I, and afterwards you got out of bed and stood there looking at me. I thought that you had forgiven me, that now we were going to go on with our lives the way they had been before. Bernice? you said. Gloria? Patricia? Jane? Rosemary? Laura? Laura? Harriet? Jocelyn? Nora? Rowena? Anthea?

I got out of bed. I put on clothes and left the room. You followed me. Marly? Genevieve? Karla? Kitty? Soibhan? Marnie? Lynley? Theresa? You said the names staccato, one after the other, like stabs. I didn't look at you, I grabbed up my car keys, and left the house. You stood in the door, watched me get in the car. Your lips were still moving, but I couldn't hear.

Tree was in front of the car and when I saw him, I swerved. I was already going too fast, halfway out of the driveway. I pinned him up against the mailbox, and then the car hit the lilac tree. White petals were raining down. You screamed. I can't remember what happened next.

I don't know if this is how I died. Maybe I died more than once, but it finally took. Here I am. I don't think this is an island. I think that I am a dead man, stuffed inside a box. When I'm quiet, I can almost hear the other dead men scratching at the walls of their boxes.

Or maybe I'm a ghost. Maybe the waves, which look like fur, are fur, and maybe the water which hisses and spits at me is really a cat, and the cat is a ghost, too.

Maybe I'm here to learn something, to do penance. The loolies have forgiven me. Maybe you will, too. When the sea comes to my hand, when it purrs at me, I'll know that you've forgiven me for what I did. For leaving you after I did it.

Or maybe I'm a tourist, and I'm stuck on this island with the loolies until it's time to go home, or until you come here to get me, Poppy? Irene? Delores? which is why I hope you get this letter.

You know who.

Tell me which you could sooner do without, love or water."

"What do you mean?"

"I mean, could you live without love, or could you live without water?"

"Why can't I have both?"

#

Rachel Rook took Carroll home to meet her parents two months after she first slept with him. For a generous girl, a girl who took off her clothes with abandon, she was remarkably close-mouthed about some things. In two months Carroll had learned that her parents lived on a farm several miles outside of town; that they sold strawberries in summer, and Christmas trees in the winter. He knew that they never left the farm; instead, the world came to them in the shape of weekend picnickers and driveby tourists.

"Do you think your parents will like me?" he said. He had spent the afternoon preparing for this visit as carefully as if he were preparing for an exam. He had gotten his hair cut, trimmed his nails, washed his neck and behind his ears. The outfit he had chosen, khaki pants and a blue button-down shirt—no tie—lay neatly folded on the bed. He stood before Rachel in his plain white underwear and white socks, gazing at her as if she were a mirror.

"No," she said. It was the first time she had been to his apartment, and she stood square in the center of his bedroom, her arms folded against her body as if she was afraid to sit down, to touch something.

"Why?"

"My father will like you," she said. "But he likes everyone. My mother's more particular—she thinks that you lack a serious nature."

Carroll put on his pants, admiring the crease. "So you've talked to her about me."

"Yes."

"But you haven't talked about her to me."

"No."

"Are you ashamed of her?"

Rachel snorted. Then she sighed in a way that seemed to suggest she was regretting her decision to take him home. "You're ashamed of me," he guessed, and Rachel kissed him and smiled and didn't say anything.

#

Rachel still lived on her parents' farm, which made it all the more remarkable that she had kept Carroll and her parents apart for so long. It suggested a talent for daily organization that filled Carroll's heart with admiration and lust. She was nineteen, two years younger than Carroll; she was a student at Jellicoh College and every weekday she rose at seven and biked four miles into town, and then back again on her bike, four miles uphill to the farm.

Carroll met Rachel in the Jellicoh College library, where he had a part-time job. He sat at the checkout desk, stamping books and reading Tristram Shandy for a graduate class; he was almost asleep when someone said, "Excuse me."

He looked up. The girl who stood before the tall desk was red-headed. Sunlight streaming in through a high window opposite her lit up the fine hairs on her arm, the embroidered flowers on the collar of her white shirt. The sunlight turned her hair to fire and Carroll found it difficult to look directly at her. "Can I help you?" he said.

She placed a shredded rectangle on the desk, and Carroll picked it up between his thumb and forefinger. Pages hung in tatters from the sodden blue spine. Title, binding, and covers had been gnawed away. "I need to pay for a damaged book," she said.

"What happened? Did your dog eat it?" he said, making a joke.

"Yes," she said, and smiled.

"What's your name?" Carroll said. Already, he thought he might be in love.

#

The farmhouse where Rachel lived had a wrap-around porch like an apron. It had been built on a hill, and looked down a long green slope of Christmas trees towards the town and Jellicoh College. It looked old-fashioned and a little forlorn.

On one side of the house was a small barn, and behind the barn was an oval pond, dark and fringed with pine trees. It winked in the twilight like a glossy lidless eye. The sun was rolling down the grassy rim of the hill towards the pond, and the exaggerated shadows of Christmas trees, long and pointed as witches' hats, stitched black triangles across the purple-grey lawn. House, barn, and hill were luminous in the fleet purple light.

Carroll parked the car in front of the barn and went around to Rachel's side to hand her out. A muffled, ferocious breathing emanated from the barn, and the doors shuddered as if something inside was hurling itself repeatedly towards them, through the dark and airless space. There was a sour animal smell. "What's in there?" Carroll asked.

"The dogs," Rachel said. "They aren't allowed in the house and they don't like to be separated from my mother."

"I like dogs," Carroll said.

#

There was a man sitting on the porch. He stood up as they approached the house and came forward to meet them. He was of medium build, and had pink-brown hair like his daughter. Rachel said, "Daddy, this is Carroll Murtaugh. Carroll, this is my daddy."

Mr. Rook had no nose. He shook hands with Carroll. His hand was warm and dry, flesh and blood. Carroll tried not to stare at Mr. Rook's face.

In actual fact, Rachel's father did have a nose, which was carved out of what appeared to be pine. The nostrils of the nose were flared slightly, as if Mr. Rook were smelling something pleasant. Copper wire ran through the bridge of the nose, attaching it to the frame of a pair of glasses; it nestled, delicate as a sleeping mouse, between the two lenses.

"Nice to meet you, Carroll," he said. "I understand that you're a librarian down at the college. You like books, do you?" His voice was deep and sonorous, as if he were speaking out of a well: Carroll was later to discover that Mr. Rook's voice changed slightly, depending on which nose he wore.

"Yes, sir," Carroll said. Just to be sure, he looked back at Rachel. As he had thought, her nose was unmistakably the genuine article. He shot her a second accusatory glance. Why didn't you tell me? She shrugged.

Mr. Rook said, "I don't have anything against books myself. But my wife can't stand 'em. Nearly broke her heart when Rachel decided to go to college." Rachel stuck out her lower lip. "Why don't you give your mother a hand, Rachel, setting the table, while Carroll and I get to know each other?"

"All right," Rachel said, and went into the house.

Mr. Rook sat down on the porch steps and Carroll sat down with him. "She's a beautiful girl," Mr. Rook said. "Just like her mother."

"Yes sir," Carroll said. "Beautiful." He stared straight ahead and spoke forcefully, as if he had not noticed that he was talking to a man with a wooden nose.

"You probably think it's odd, don't you, a girl her age, still living at home."

Carroll shrugged. "She seems attached to both of you. You grow Christmas trees, sir?"

"Strawberries too," Mr. Rook said. "It's a funny thing about strawberries and pine trees. People will pay you to let them dig up their own. They do all the work and then they pay you for it. They say the strawberries taste better that way, and they may be right. Myself, I can't taste much anyway."

Carroll leaned back against the porch rail and listened to Mr. Rook speak. He sneaked sideways looks at Mr. Rook's profile. From a few feet away, in the dim cast of the porch light, the nose had a homely, thoughtful bump to it: it was a philosopher's nose, a questing nose. White moths large as Carroll's hand pinwheeled around the porch light. They threw out tiny halos of dark and stirred up breaths of air with their wings, coming to rest on the porch screen, folding themselves into stillness like fans. Moths have no noses either, Carroll thought.

"I can't smell the pine trees either," Mr. Rook said. "I have to appreciate the irony in that. You'll have to forgive my wife, if she seems a bit awkward at first. She's not used to strangers."

Rachel danced out onto the porch. "Dinner's almost ready," she said. "Has Daddy been keeping you entertained?"

"He's been telling me all about your farm," Carroll said.

Rachel and her father looked at each other thoughtfully. "That's great," Rachel said. "You know what he's really dying to ask, Daddy. Tell him about your collection of noses."

"Oh no," Carroll protested. "I wasn't wondering at all—"

But Mr. Rook stood up, dusting off the seat of his pants. "I'll go get them down. I almost wore a fancier one tonight, but it's so windy tonight, and rather damp. I didn't trust it not to rain." He hurried off into the house.

Carroll leaned over to Rachel. "Why didn't you tell me?" he said, looking up at her from the porch rail.

"What?"

"That your father has a wooden nose."

"He has several noses, but you heard him. It might rain. Some of them," she said, "are liable to rust."

"Why does he have a wooden nose?" Carroll said. He was whispering.

"A boy named Biederbecke bit it off, in a fight." The alliteration evidently pleased her, because she said a little louder, "Biederbecke bit it off, when you were a boy. Isn't that right, Daddy?"

The porch door swung open again, and Mr. Rook said, "Yes, but I don't blame him, really I don't. We were little boys and I called him a stinking Kraut. That was during the war, and afterwards he was very sorry. You have to look on the bright side of things—your mother would never have noticed me if it hadn't had been for my nose. That was a fine nose. I modeled it on Abraham Lincoln's nose, and carved it out of black walnut." He set a dented black tackle box down next to Carroll, squatting beside it. "Look here."

The inside of the tackle box was lined with red velvet and the mild light of the October moon illuminated the noses, glowing as if a jeweler's lamp had been turned upon them: noses made of wood, and beaten copper, tin and brass. One seemed to be silver, veined with beads of turquoise. There were aquiline noses; noses pointed like gothic spires; noses with nostrils curled up like tiny bird claws.

"Who made these?" Carroll said.

Mr. Rook coughed modestly. "It's my hobby," he said. "Pick one up if you like."

"Go ahead," Rachel said to Carroll.

Carroll chose a nose that had been painted over with blue and pink flowers. It was glassy-smooth and light in his hand, like a blown eggshell. "It's beautiful," he said. "What's it made out of?"

"Papier-mache. There's one for every day of the week." Mr. Rook said.

"What did the … original look like?" Carroll asked.

"Hard to remember, really. It wasn't much of a nose," Mr. Rook said. "Before."

#

"Back to the question, please. Which do you choose, water or love?"

"What happens if I choose wrong?"

"You'll find out, won't you."

"Which would you choose?"

"That's my question, Carroll. You already asked yours."

"You still haven't answered me, either. All right, all right, let me think for a bit."

#

Rachel had straight reddish-brown hair that fell precisely to her shoulders and then stopped. Her eyes were fox-colored, and she had more small, even teeth than seemed absolutely necessary to Carroll. She smiled at him, and when she bent over the tacklebox full of noses, Carroll could see the two wings of her shoulderblades beneath the thin cotton T-shirt, her vertebrae outlined like a knobby strand of coral. As they went in to dinner she whispered in his ear, "My mother has a wooden leg."

She led him into the kitchen to meet her mother. The air in the kitchen was hot and moist and little beads of sweat stood out on Mrs. Rook's face. Rachel's mother resembled Rachel in the way that Mr. Rook's wooden nose resembled a real nose, as if someone had hacked Mrs. Rook out of wood or granite. She had large hands with long, yellowed fingernails, and all over her black dress were short black dog hairs. "So you're a librarian," she said to Carroll.

"Part-time," Carroll said. "Yes, ma'am."

"What do you do the rest of the time?" she said.

"I take classes."

Mrs. Rook stared at him without blinking. "Are your parents still alive?"

"My mother is," Carroll said. "She lives in Florida. She plays bridge."

Rachel grabbed Carroll's arm. "Come on," she said. "The food's getting cold."

She pulled him into a dining room with dark wood paneling and a long table set for four people. The long black hem of Mrs. Rook's dress hissed along the floor as she pulled her chair into the table. Carroll sat down next to her. Was it the right or the left? He tucked his feet under his chair. Both women were silent and Carroll was silent between them. Mr. Rook talked instead, filling in the awkward empty pause so that Carroll was glad that it was his nose and not his tongue that the Biederbecke boy had bitten off.

How had she lost her leg? Mrs. Rook watched Carroll with a cold and methodical eye as he ate, and he held Rachel's hand under the table for comfort. He was convinced that her mother knew this and disapproved. He ate his pork and peas, balancing the peas on the blade of his knife. He hated peas. In between mouthfuls, he gulped down the pink wine in his glass. It was sweet and strong and tasted of burnt sugar. "Is this apple wine?" he asked. "It's delicious."

"It's strawberry wine," Mr. Rook said, pleased. "Have more. We make up a batch every year. I can't taste it myself but it's strong stuff."

Rachel filled Carroll's empty glass and watched him drain it instantly. "If you've finished, why don't you let my mother take you to meet the dogs? You look like you could use some fresh air. I'll stay here and help Daddy do the dishes. Go on," she said. "Go."

Mrs. Rook pushed her chair back from the table, pushed herself out of the chair. "Well, come on," she said. "I don't bite."

Outside, the moths beat at his face, and he reeled beside Rachel's mother on the moony-white gravel, light as a thread spun out on its spool. She walked quickly, leaning forward a little as her right foot came down, dragging the left foot through the small stones.

"What kind of dogs are they?" he said.

"Black ones," she said.

"What are their names?"

"Flower and Acorn," she said, and flung open the barn door. Two Labradors, slippery as black trout in the moonlight, surged up at Carroll. They thrust their velvet muzzles at him, uttering angry staccato coughs, their rough breath steaming at his face. They were the size of small ponies and their paws left muddy prints on his shirt. Carroll pushed them back down, and they snapped at his hands.

"Heel," Mrs. Rook said, and instantly the two dogs went to her, arranging themselves on either side like bookends. Against the folds of her skirt, they were nearly invisible, only their saucer-like eyes flashing wickedly at Carroll.

"Flower's pregnant," Mrs. Rook said. "We've tried to breed them before, but it never took. Go for a run, girl. Go with her, Acorn."

The dogs loped off, moonlight spilling off their coats like water. Carroll watched them run; the stale air of the barn washed over him, and under the bell of Mrs. Rook's skirt he pictured the dark wood of the left leg, the white flesh of the right leg, like a pair of mismatched dice. Mrs. Rook drew in her breath. She said, "I don't mind you sleeping with my daughter but you had better not get her pregnant." Carroll said,

"No, ma'am." "If you give her a bastard, I'll set the dogs on you," she said, and went back towards the house. Carroll scrambled after her.

#

On Friday, Carroll was shelving new books on the third floor. He stood, both arms lifted up to steady a wavering row of psychology periodicals. Someone paused in the narrow row, directly behind him, and a small cold hand insinuated itself into his trousers, slipping under the waistband of his underwear.

"Rachel?" he said, and the hand squeezed, slowly. He jumped and the row of books toppled off their shelf, like dominoes. He bent to pick them up, not looking at her. "I forgive you," he said.

"That's nice," she said. "For what?" "For not telling me about your father's—" he hesitated, looking for the word, "—wound."

"I thought you handled that very well," she said. "And I did tell you about my mother's leg."

"I wasn't sure whether or not to believe you. How did she lose it?"

"She swims down in the pond. She was walking back up to the house. She was barefoot. She sliced her foot open on something. By the time she went to see a doctor, she had septicemia and her leg had to be amputated just below the knee. Daddy made her a replacement out of walnut; he said the prosthesis that the hospital wanted to give her looked nothing like the leg she'd lost. It has a name carved on it. She used to tell me that a ghost lived inside it and helped her walk. I was four years old." She didn't look at him as she spoke, flicking the dust off the spine of a tented book with her long fingers.

"What was its name?" Carroll asked.

"Ellen," Rachel said.

#

Two days after they had first met, Carroll was in the basement stacks. It was dark in the aisles, the tall shelves curving towards each other. The lights were controlled by timers, and went on and off untouched by human hand: there was the ominous sound of ticking as the timers clicked off row by row. Puddles of dirty yellow light wavered under his feet, the floor as slick as water. There was one other student on this floor, a boy who trod at Carroll's heels, breathing heavily.

Rachel was in a back corner, partly hidden by a shelving cart. "Goddammit, goddammit to hell," she was saying, as she flung a book down. "Stupid book, stupid, useless, stupid, know-nothing books." She kicked at the book several more times, and stomped on it for good measure. Then she looked up and saw Carroll and the boy behind him. "Oh," she said. "You again." Carroll turned and glared at the boy. "What's the matter," he said. "Haven't you ever seen a librarian at work?"

The boy fled. "What's the matter?" Carroll said again.

"Nothing," Rachel said. "I'm just tired of reading stupid books about books about books. It's ten times worse then my mother ever said." She looked at him, weighing him up. She said, "Have you ever made love in a library?"

"Um," Carroll said. "No."

Rachel stripped off her woolly sweater, her blue undershirt. Underneath, her bare flesh burned. The lights clicked off two rows down, then the row beside Carroll, and he moved forward to find Rachel before she vanished. Her body was hot and dry, like a newly extinguished bulb.

Rachel seemed to enjoy making love in the library. The library officially closed at midnight, and on Tuesdays and Thursdays when he was the last of the staff to leave, Carroll left the East Entrance unlocked for Rachel while he made up a pallet of jackets and sweaters from the Lost and Found.

The first night, he had arranged a makeshift bed in the aisle between PR878W6B37, Relative Creatures, and PR878W6B35, Corrupt Relations. In the summer, the stacks had been much cooler than his un-air-conditioned room. He had hoped to woo her into his bed by the time the weather turned, but it was October already. Rachel pulled PR878W6A9 out to use as a pillow. "I thought you didn't like books," he said, trying to make a joke.

"My mother doesn't like books," she said. "Or libraries. Which is a good thing. You don't ever have to worry about her looking for me here."

When they made love, Rachel kept her eyes closed. Carroll watched her face, her body rocking beneath him like water. He closed his eyes, opening them quickly again, hoping to catch her looking back at him. Did he please her? He pleased himself, and her breath quickened upon his neck. Her hands smoothed his body, moving restlessly back and forth, until he gathered them to himself, biting at her knuckles.

Later he lay prone as she moved over him, her knees clasping his waist, her narrow feet cupped under the stirrups of his knees. They lay hinged together and Carroll squinted his eyes shut to make the Exit sign fuzzy in the darkness. He imagined that they had just made love in a forest, and the red glow was a campfire. He imagined they were not on the third floor of a library, but on the shore of a deep, black lake in the middle of a stand of tall trees.

"When you were a teenager," Rachel said, "what was the worst thing you ever did?"

Carroll thought for a moment. "When I was a teenager," he said, "I used to go into my room every day after school and masturbate. And my dog Sunny used to stand outside the door and whine. I'd come in a handful of Kleenex, and afterward I never knew what to do with them. If I threw them in the wastebasket, my mother might notice them piling up. If I dropped them under the bed, then Sunny would sneak in later and eat them. It was a revolting dilemma, and every day I swore I wouldn't ever do it again."

"That's disgusting, Carroll."

Carroll was constantly amazed at the things he told Rachel, as if love was some sort of hook she used to drag secrets out of him, things that he had forgotten until she asked for them. "Your turn," he said.

Rachel curled herself against him. "Well, when I was little, and I did something bad, my mother used to take off her wooden leg and spank me with it. When I got older, and started being asked out on dates, she would forbid me. She actually said I forbid you to go, just like a Victorian novel. I would wait until she took her bath after dinner, and steal her leg and hide it. And I would stay out as late as I wanted. When I got home, she was always sitting at the kitchen table, with the leg strapped back on. She always found it before I got home, but I always stayed away as long as I could. I never came home before I had to.

"When I was little I hated her leg. It was like her other child, the obedient daughter. I was the one she had to spank. I thought the leg told her when I was bad, and I could feel it gloating whenever she punished me. I hid it from her in closets, or in the belly of the grandfather clock. Once I buried it out in the strawberry field because I knew it hated the dark: it was scared of the dark, like me."

Carroll eased away from her, rolling over on his stomach. The whole time she had been talking, her voice had been calm, her breath tickling his throat. Telling her about Sunny, the semen-eating dog, he had sprouted a cheerful little erection. Listening to her, it had melted away, and his balls had crept up his goose-pimpled thighs.

Somewhere a timer clicked and a light turned off. "Let's make love again," she said, and seized him in her hand. He nearly screamed.

#

In late November, Carroll went to the farm again for dinner. He parked just outside the barn, where, malignant and black as tar, Flower lolled on her side in the cold dirty straw. She was swollen and too lazy to do more than show him her teeth; he admired them. "How pregnant is she?" Carroll asked Mr. Rook, who had emerged from the barn.

"She's due any day," Mr. Rook said. "The vet says there might be six puppies in there." Today he wore a tin nose, and his words had a distinct echo, whistling out double shrill, like a teakettle on the boil. "Would you like to see my workshop?" he said.

"Okay," Carroll said. The barn smelled of gasoline and straw, old things congealing in darkness; it smelled of winter. Along the right inside wall, there were a series of long hooks, and depending from them were various pointed and hooked tools. Below was a table strewn with objects that seemed to have come from the city dump: bits of metal; cigar boxes full of broken glass sorted according to color; a carved wooden hand, jointed and with a dime-store ring over the next-to-last finger.

Carroll picked it up, surprised at its weight. The joints of the wooden fingers clicked as he manipulated them, the fingers long and heavy and perfectly smooth. He put it down again. "It's very nice," he said and turned around. Through the thin veil of sunlight and dust that wavered in the open doors, Carroll could see a black glitter of water. "Where's Rachel?"

"She went to find her mother, I'll bet. They'll be down by the pond. Go and tell them it's dinner time." Mr. Rook looked down at the black and rancorous Flower. "Six puppies!" he remarked, in a sad little whistle.

Carroll went down through the slanted grove of Christmas trees. At the base of the hill was a circle of twelve oaks, their leaves making a thick carpet of gold. The twelve trees were spaced evenly around the perimeter of the pond, like the numbers on a clock face. Carroll paused under the eleven o'clock oak, looking at the water. He saw Rachel in the pond, her white arm cutting through the gaudy leaves that clung like skin, bringing up black droplets of water. Carroll stood in his corduroy jacket and watched her swim laps across the pond. He wondered how cold the water was. Then he realized that it wasn't Rachel in the pond.

Rachel sat on a quilt on the far side of the pond, under the six o'clock oak. Acorn sat beside her, looking now at the swimmer, now at Carroll. Rachel and her mother were both oblivious to his presence, Mrs. Rook intent on her exercise, Rachel rubbing linseed oil into her mother's wooden leg. The wind carried the scent of it across the pond. The dog stood, stiff-legged, fixing Carroll in its dense liquid gaze. It shook itself, sending up a spray of water like diamonds.

"Cut it out, Acorn!" Rachel said without looking up. All the way across the pond, Carroll felt the drops of water fall on him, cold and greasy.

He felt himself turning to stone with fear. He was afraid of the leg that Rachel held in her lap. He was afraid that Mrs. Rook would emerge from her pond, and he would see the space where her knee hung above the ground. He backed up the hill slowly, almost falling over a small stone marker at the top. As he looked at it, the dog came running up the path, passing him without a glance, and after that, Rachel, and her mother, wearing the familiar black dress. The ground was slippery with leaves and Mrs. Rook leaned on her daughter. Her hair was wet and her cheeks were as red as leaves.

"I can't read the name," Carroll said. "It's Ellen," Mrs. Rook said. "My husband carved it." Carroll looked at Rachel. Your mother has a tombstone for her leg?Rachel looked away.

#

"You can't live without water."

"So that's your choice?"

"I'm just thinking out loud. I know what you want me to say."

No answer.

"Rachel, look. I choose water, okay?"

No answer.

"Let me explain. You can lie to water—you can say no, I'm not in love, I don't need love, and you can be lying—how is the water supposed to know that you're lying? It can't tell if you're in love or not, right? Water's not that smart. So you fool the water into thinking you'd never dream of falling in love, and when you're thirsty, you drink it."

"You're pretty sneaky."

"I love you, Rachel. Will you please marry me? Otherwise your mother is going to kill me."

No answer.

#

After dinner, Carroll's car refused to start. No one answered when they rang a garage, and Rachel said, "He can take my bike, then."

"Don't be silly," Mr. Rook said. "He can stay here and we'll get someone in the morning. Besides, it's going to rain soon."

"I don't want to put you to any trouble," Carroll said.

Rachel said, "It's getting dark. He can call a taxi." Carroll looked at her, hurt, and she frowned at him.

"He'll stay in the back room," Mrs. Rook said. "Come and have another glass of wine before you go to bed, Carroll." She grinned at him in what might have been a friendly fashion, except that at some point after dinner, she had removed her dentures.

Rachel brought him a pair of her father's pajamas and led him off to the room where he was to sleep. The room was small and plain and the only beautiful thing in it was Rachel, sitting on a blue and scarlet quilt. "Who made this?" he said.

"My mother did," Rachel said. "She's made whole closetsful of quilts. It's what she used to do while she waited for me to get home from a date. Now get in bed."

"Why didn't you want me to spend the night?" he asked.

She stuck a long piece of hair in her mouth, and sucked on it, staring at him without blinking. He tried again. "How come you never spend the night at my apartment?"

She shrugged. "Are you tired?"

Carroll yawned, and gave up. "Yes," he said and Rachel kissed him goodnight. It was a long, thoughtful kiss. She turned out the light and went down the hall to her own bedroom. Carroll rolled on his side and fell asleep and dreamed that Rachel came back in the room and stood naked in the moonlight. Then she climbed in bed with him and they made love and then Mrs. Rook came into the room. She beat at them with her leg as they hid under the quilt. She struck Rachel and turned her into wood.

As Carroll left the next morning, it was discovered that Flower had given birth to seven puppies in the night. "Well, it's too late now," Rachel said.

"Too late for what?" Carroll asked. His car started on the first try.

"Never mind," Rachel said gloomily. She didn't wave as he drove away.

#

Carroll discovered that if he said "I love you," to Rachel, she would say "I love you too," in an absent-minded way. But she still refused to come to his apartment, and because it was colder now, they made love during the day, in the storage closet on the third floor. Sometimes he caught her watching him now, when they made love. The look in her eyes was not quite what he had hoped it would be, more shrewd than passionate. But perhaps this was a trick of the cold winter light.

Sometimes, now that it was cold, Rachel let Carroll drive her home from school. The sign beside the Rooks' driveway now said, "Get your Christmas Trees early." Beneath that it said, "Adorable black Lab Puppies free to a Good home."

But no one wanted a puppy. This was understandable; already the puppies had the gaunt, evil look of their parents. They spent their days catching rats in the barn, and their evenings trailing like sullen shadows around the black skirts of Mrs. Rook. They tolerated Mr. Rook and Rachel; Carroll they eyed hungrily.

"You have to look on the bright side," Mr. Rook said. "They make excellent watchdogs."

#

Carroll gave Rachel a wooden bird on a gold chain for Christmas, and the complete works of Jane Austen. She gave him a bottle of strawberry wine and a wooden box, with six black dogs painted on the lid. They had fiery red eyes and red licorice tongues. "My father carved it, but I painted it," she said.

Carroll opened the box. "What will I put in it?" he said.

Rachel shrugged. The library was closed for the weekend, and they sat on the dingy green carpet in the deserted lounge. The rest of the staff was on break, and Mr. Cassatti, Carroll's supervisor, had asked Carroll to keep an eye on things.

There had been some complaints, he said, of vandalism in the past few weeks. Books had been knocked off their shelves, or disarranged, and even more curious, a female student claimed to have seen a dog up on the third floor. It had growled at her, she said, and then slunk off into the stacks. Mr. Cassatti, when he had gone up to check, had seen nothing. Not so much as a single hair. He wasn't worried about the dog, Mr. Cassatti had said, but some books had been discovered, the pages ripped out. Maimed, Mr. Cassatti had said.

Rachel handed Carroll one last parcel. It was wrapped in a brown paper bag, and when he opened it, a blaze of scarlet and cornflower blue spilled out onto his lap. "My mother made you a quilt just like the one in the spare bedroom," Rachel said. "I told her you thought it was pretty."

"It's beautiful," Carroll said. He snapped the quilt out, so that it spread across the library floor, as if they were having a picnic. He tried to imagine making love to Rachel beneath a quilt her mother had made. "Does this mean that you'll make love with me in a bed?"

"I'm pregnant," Rachel said.

He looked around to see if anyone else had heard her, but of course they were alone. "That's impossible," he said. "You're on the pill."

"Yes, well." Rachel said. "I'm pregnant anyway. It happens sometimes."

"How pregnant?" he asked.

"Three months."

"Does your mother know?"

"Yes," Rachel said.

"Oh God, she's going to put the dogs on me. What are we going to do?"

"What am I going to do," Rachel said, looking down at her cupped hands so that Carroll could not see her expression. "What am I going to do," she said again.

There was a long pause and Carroll took one of her hands in his. "Then we'll get married?" he said, a quaver in his voice turning the statement into a question.

"No," she said, looking straight at him, the way she looked at him when they made love. He had never noticed what a sad hopeless look this was.

Carroll dropped his own eyes, ashamed of himself and not quite sure why. He took a deep breath. "What I meant to say, Rachel, is I love you very much and would you please marry me?"

Rachel pulled her hand away from him. She said in a low angry voice, "What do you think this is, Carroll? Do you think this is a book? Is this supposed to be the happy ending—we get married and live happily ever after?"

She got up, and he stood up too. He opened his mouth, and nothing came out, so he just followed her as she walked away. She stopped so abruptly that he almost fell against her. "Let me ask you a question first," she said, and turned to face him. "What would you choose, love or water?"

The question was so ridiculous that he found he was able to speak again. "What kind of a question is that?" he said.

"Never mind. I think you better take me home in your car," Rachel said. "It's starting to snow."

Carroll thought about it during the car ride. He came to the conclusion that it was a silly question, and that if he didn't answer it correctly, Rachel wasn't going to marry him. He wasn't entirely sure that he wanted to give the correct answer, even if he knew what it was.

He said, "I love you, Rachel." He swallowed and he could hear the snow coming down, soft as feathers on the roof and windshield of the car. In the two beams of the headlights the road was dense and white as an iced cake, and in the reflected snow-light Rachel's face was a beautiful greenish color. "Will you marry me anyway? I don't know how you want me to choose."

"No."

"Why not?" They had reached the farm; he turned the car into driveway, and stopped.

"You've had a pretty good life so far, haven't you?" she said.

"Not too bad," he said sullenly.

"When you walk down the street," Rachel said, "do you ever find pennies?"

"Yes," he said.

"Are they heads or tails?"

"Heads, usually," he said.

"Do you get good grades?"

"As and Bs," he said.

"Do you have to study hard? Have you ever broken a mirror? When you lose things," she said, "do you find them again?"

"What is this, an interview?"

Rachel looked at him. It was hard to read her expression, but she sounded resigned. "Have you ever even broken a bone? Do you ever have to stop for red lights?"

"Okay, okay," he snapped. "My life is pretty easy. I've gotten everything I ever wanted for Christmas, too. And I want you to marry me, so of course you're going to say yes."

He reached out, put his arms around her. She sat brittle and stiff in the circle of his embrace, her face turned into his jacket. "Rachel—"

"My mother says I shouldn't marry you," she said. "She says I don't really know you, that you're feckless, that you've never lost anything that you cared about, that you're the wrong sort to be marrying into a family like ours."

"Is your mother some kind of oracle, because she has a wooden leg?"

"My mother knows about losing things," Rachel said, pushing at him. "She says it'll hurt, but I'll get over you."

"So tell me, how hard has your life been?" Carroll said. "You've got your nose, and both your legs. What do you know about losing things?"

"I haven't told you everything," Rachel said and slipped out of the car. "You don't know everything about me." Then she slammed the car door. He watched her cross the driveway and go up the hill into the snow.

Carroll called in sick all the next week. The heating unit in his apartment wasn't working, and the cold made him sluggish. He thought about going in to the library, just to be warm, but instead he spent most of his time under the quilt that Mrs. Rook had made, hoping to dream about Rachel. He dreamed instead about being devoured by dogs, about drowning in icy black water.

He lay in his dark room, under the weight of the scarlet quilt, when he wasn't asleep, and held long conversations in his head with Rachel, about love and water. He told her stories about his childhood; she almost seemed to be listening. He asked her about the baby and she told him she was going to name it Ellen if it was a girl. When he took his own temperature on Wednesday, the thermometer said he had a fever of 103, so he climbed back into bed.

When he woke up on Thursday morning, he found short black hairs covering the quilt, which he knew must mean that he was hallucinating. He fell asleep again and dreamed that Mr. Rook came to see him. Mr. Rook was a Black Lab. He was wearing a plastic Groucho Marx nose. He and Carroll stood beside the black lake that was on the third floor of the library.

The dog said, "You and I are a lot alike, Carroll."

"I suppose," Carroll said.

"No, really," the dog insisted. It leaned its head on Carroll's knee, still looking up at him. "We like to look on the bright side of things. You have to do that, you know."

"Rachel doesn't love me anymore," Carroll said. "Nobody likes me." He scratched behind Mr. Rook's silky ear.

"Now, is that looking on the bright side of things?" said the dog. "Scratch a little to the right. Rachel has a hard time, like her mother. Be patient with her."

"So which would you choose," Carroll said. "Love or water?"

"Who says anyone gets to choose anything? You said you picked water, but there's good water and there's bad water. Did you ever think about that?" the dog said. "I have a much better question for you. Are you a good dog or a bad dog?"

"Good dog!" Carroll yelled, and woke himself up.

He called the farmhouse in the morning, and when Rachel answered, he said, "This is Carroll. I'm coming to talk to you."

But when he got there, no one was there. The sight of the leftover Christmas trees, tall and gawky as green geese, made him feel homesick. Little clumps of snow like white flowers were melting in the gravel driveway. The dogs were not in the barn and he hoped that Mrs. Rook had taken them down to the pond.

He walked up to the house, and knocked on the door. If either of Rachel's parents came to the door, he would stand his ground and demand to see their daughter. He knocked again, but no one came. The house, shuttered against the snow, had an expectant air, as if it were waiting for him to say something. So he whispered, "Rachel? Where are you?" The house was silent. "Rachel, I love you. Please come out and talk to me. Let's get married—we'll elope. You steal your mother's leg, and by the time your father carves her a new one, we'll be in Canada. We could go to Niagara Falls for our honeymoon—we could take your mother's leg with us, if you want—Ellen, I mean—we'll take Ellen with us!"

Carroll heard a delicate cough behind him as if someone were clearing their throat. He turned and saw Flower and Acorn and their six enormous children sitting on the gravel by the barn, next to his car. Their fur was spiky and wet, and they curled their black lips at him. Someone in the house laughed. Or perhaps it was the echo of a splash, down at the pond.

One of the dogs lifted its head and bayed at him. "Hey," he said. "Good dog! Good Flower, good Acorn! Rachel, help!"

She had been hiding behind the front door. She slammed it open and came out onto the porch. "My mother said I should just let the dogs eat you," she said. "If you came."

She looked tired; she wore a shapeless woolen dress that looked like one of her mother's. If she really was pregnant, Carroll couldn't see any evidence yet. "Do you always listen to your mother?" he said. "Don't you love me?"

"When I was born," she said. "I was a twin. My sister's name was Ellen. When we were seven years old, she drowned in the pond—I lost her. Don't you see? People start out losing small things, like noses. Pretty soon you start losing other things too. It's sort of an accidental leprosy. If we got married, you'd find out."

Carroll heard someone coming up the path from the pond, up through the thin ranks of Christmas trees. The dogs pricked up their ears, but their black eyes stayed fastened to Carroll. "You'd better hurry," Rachel said. She escorted him past the dogs to his car.

"I'm going to come back."

"That's not a good idea," she said. The dogs watched him leave, crowding close around her, their black tails whipping excitedly. He went home and in a very bad temper, he picked up the quilt to inspect it. He was looking for the black hairs he had seen that morning. But of course there weren't any.

The next day he went back to the library. He was lifting books out of the overnight collection box, when he felt something that was neither rectangular nor flat. It was covered in velvety fur, and damp. He felt warm breath steaming on his hand. It twisted away when he tried to pick it up, and when he reached out for it again, it snarled at him.

He backed away from the collection box, and a long black dog wriggled out of the box after him. Two students stopped to watch what was happening. "Go get Mr. Cassatti, please," Carroll said to one of them. "His office is around the corner."

The dog approached him. Its ears were laid back flat against its skull and its neck moved like a snake.

"Good dog?" Carroll said, and held out his hand. "Flower?" The dog lunged forward and, snapping its jaws shut, bit off his pinky just below the fingernail.

The student screamed. Carroll stood still and looked down at his right hand, which was slowly leaking blood. The sound that the dog's jaw had made as it severed his finger had been crisp and businesslike. The dog stared at Carroll in a way that reminded him of Rachel's stare. "Give me back my finger," Carroll said.

The dog growled and backed away. "We have to catch it," the student said. "So they can reattach your finger. Shit, what if it has rabies?"

Mr. Cassatti appeared, carrying a large flat atlas, extended like a shield. "Someone said that there was a dog in the library," he said.

"In the corner over there," Carroll said. "It bit off my finger." He held up his hand for Mr. Cassatti to see, but Mr. Cassatti was looking towards the corner and shaking his head.

He said, "I don't see a dog."

The two students hovered, loudly insisting that they had both seen the dog a moment ago, while Mr. Cassatti tended to Carroll. The floor in the corner was sticky and wet, as if someone had spilled a Coke. There was no sign of the dog.

Mr. Cassatti took Carroll to the hospital, where the doctor at the hospital gave him a shot of codeine, and tried to convince him that it would be a simple matter to reattach the fingertip. "How?" Mr. Cassatti said. "He says the dog ran away with it."

"What dog?" the doctor asked.

"It was bitten off by a dog," Carroll told the doctor.

The doctor raised his eyebrows. "A dog in a library? This looks like he stuck his finger under a paper cutter. The cut is too tidy—a dog bite would be a mess. Didn't anyone bring the finger?"

"The dog ate it," Carroll said. "Mrs. Rook said the dog would eat me, but it stopped. I don't think it liked the way I tasted."

Mr. Cassatti and the doctor went out into the hall to discuss something. Carroll stood at the door and waited until they had turned towards the nurses' station. He opened the door and snuck down the hallway in the opposite direction and out of the hospital. It was a little hard, walking on the ground—the codeine seemed to affect gravity. When he walked, he bounced. When walking got too difficult, he climbed in a taxi and gave the driver the address of the Rook farm.

His hand didn't hurt at all; he tried to remember this, so he could tell Rachel. They had bound up his hand in white gauze bandages, and it looked like someone else's hand entirely. Under the white bandages, his hand was pleasantly warm. His skin felt stretched, tight and thin as a rubber glove. He felt much lighter: it might take a while, but he thought he could get the hang of losing things; it seemed to come as easily to him as everything else did.

Carroll thought maybe Rachel and he would get married down by the pond, beneath the new leaves of the six o'clock oak tree. Mr. Rook could wear his most festive nose, the one with rose-velvet lining, or perhaps the one painted with flowers. Carroll remembered the little grave at the top of the path that led to the pond—not the pond, he decided—they should be married in a church. Maybe in a library.

"Just drop me off here," he told the taxi driver at the top of the driveway.

"Are you sure you'll be okay?" the driver said. Carroll shook his head, yes, he was sure. He watched the taxi drive away, waving the hand with the abbreviated finger.

Mrs. Rook could make her daughter a high-waisted wedding dress, satin and silk and lace, moth-pale, and there would be a cake with eight laughing dogs made out of white frosting, white as snow. For some reason he had a hard time making the church come out right. It kept changing, church into library, library into black pond. The windows were high and narrow and the walls were wet like the inside of a well. The aisle kept changing, the walls getting closer, becoming stacks of books, dark, velvety waves. He imagined standing at the altar with Rachel—black water came up to their ankles as if their feet had been severed. He thought of the white cake again: if he sliced into it, darkness would gush out like ink.

He shook his head, listening. There was a heavy dragging noise, coming up the side of the hill through the Christmas trees. It would be a beautiful wedding and he considered it a lucky thing that he had lost his pinky and not his ring finger. You had to look on the bright side after all. He went down towards the pond, to tell Rachel this.