J. W. Benson – UK Provincial Theatre Actor in the Victorian Era

INTRODUCTION

When I was investigating the story of the life of Clementine Benson, I touched briefly on information the family had about her first husband, John Whitehead / Benson. At that time, I had him tabbed as a bit of a rogue, but because he and Clementine separated after only a few years of marriage, he didn’t really feature in that saga.

Since then, I have delved more deeply into his life, and discovered that his being an actor meant that I was able to uncover a wealth of information about him, thanks to the countless newspapers from that era that are available on the British Newspapers website.

Some of the information we were handed down has now become fact; other details had been glossed over, and a few were definite misinformation. Whether the latter were fabrications, or whether they changed with the mists of time, now I feel confident that facts I write here can be verified from those newspaper sources. Of course, newspaper content can’t be assumed to be gospel truth, but when it can be verified from more than one source, it becomes more acceptable in my eyes. I don’t claim to know all there is to be known about the man – in some ways he’s become more of an enigma, the more I’ve uncovered about his life. It would be so fascinating to be able to sit and talk with him, but here’s the next best thing that I can offer.

One of the most difficult aspects of tracing John’s life is the fact that he managed to swing between surnames with the greatest of ease. To begin with, I wasn’t at all confident that John Benson, John Whitehead and Mr. J. W. Benson were one and the same person. Suffice to say that now, after many months of research, I’ve come across enough cross-referencing of particular events to make me confident that all three are the great-great-grandfather of my generation.

My initial points of reference were the marriage certificate of John and Clementine – here he used the surname Whitehead on 21 November 1860. One month earlier, 21 on October 1860 he again gave the surname Whitehead on the birth certificate of his son Robert (our great-grandfather). Yet Robert spent his life using the surname Benson. Family oral history was told that when Robert applied for his birth certificate prior to his marriage, he was most disturbed to find it had the surname Whitehead. Correspondence from Clementine to Robert at that time shows that John had told her there used to be a famous Shakespearian actor of that name, so he had decided to adopt the surname Benson because of that. As this story unfolds, you will see that this is one of those partial truths that have emerged.

To start at the very beginning in this story is not a wise decision. Our great-great-grandfather was such an elusive figure in so many ways, it’s much better to begin with a piece of concrete information.

We already know that Clementine Enoch married John Whitehead in November 1860. So I’ve chosen to start with their lives together, at the point of the 1861 UK Census. This data shows that on Sunday 7 April the family was residing in a Freemason’s Tavern, at 34 Bridge Street, St Mary Le Port, Bristol. Among the 12 residents on that night were the owner, his wife and 3 staff members. Our little family consisted of John B Whitehead, age 58, boarder, comedian, born Knaresborough, Yorkshire. Also his wife Clementine, age 31, actress, Caroline B Whitehead, age 10, actress, and Robert B Whitehead, age 6 months.

This was the first I had heard of Caroline, and her being an actress at the age of 10 really piqued my interest. So to the British Newspaper website. What a treasure trove that doorway proved to open! In the mid-1800s, people were becoming better educated, and playbills and newspapers were the popular advertising media of that time. When a new troupe was due in town, the theatre manager would notify the local newspapers, placing long advertisements about their shows. Once performances began, lengthy reviews were written, so spreading the word to potential customers. Now I was able to trace the career of this young lady. I think she’s an important link to our John, so we’ll cover her life, then get back to the true hero of this story.

CAROLINE MATILDA BENSON

Caroline had first appeared on the stage in South Shields, Newcastle in 1857. Here’s the piece from The Era, the performance newspaper of that time:

The Era - Sunday 8 February 1857: SOUTH SHIELDS.-The theatre was opened on Tuesday evening under the management of Mr. J. W. Benson. The pieces selected were Sir Lytton Balswer's admired play of Richelieu or, The Conspiracy, concluding with the laughable farce of The Swiss Cottage. The company comprised Mr. Benson, Mr. J. 0. Sullivan, Mr. It. Stoddart, Mr. J. Robertson Mr Ronget, Mr. Burton. Mr. Wood, Mr. Percy, Mr. Fisher, Mr. Linden, Mr J. C. Whitehouse, Mr. W. L. Webb, Mr. G. Dunn, and Mr. G. Ball. Mrs R. Stoddart, Miss Watson, Mrs. De Clifford, Mrs. Robertson, Mrs. Burton, Mrs. Bruce, Mrs. Webb, and Miss Caroline Benson. The company are most efficient, and considering the esteem in which Mr. Benson is held in South Shields, a successful season may be anticipated.

This article gave two main pieces of information – Miss Caroline Benson was performing on stage as a 6 year old, and her father, under the title Mr. J. W. Benson, was both manager and actor. To trace his career backwards from this date, and into the future was made so much easier now.

Caroline Matilda had been born on 2 December 1850, to John Whitehead Benson and Caroline Benson formerly Robinson. John was a Comedian residing at Old Chapel Lane, Alnwick, Northumberland; this is where the birth had taken place. Her mother being noted as ‘formerly’ Robinson suggests that she and John were married, although I can’t find any record of her marrying either a John Benson or John Whitehead.

At this point, a newspaper search of young Caroline’s name brought surprising results. She became quite the darling of performances; a child of her age must have proved to be a star attraction for our John.

After that first performance in 1857, Caroline must have appeared in a number of performances at South Shields and Durham Theatres. Both of these shows were being managed (and acted in) by Mr. J. W. Benson. By July 1857 it was announced that Miss Caroline Benson had taken her benefit night – she had been playing The Fairy Queen at Durham Theatre. Mr J. W. Benson had been granted a licence for that theatre in May, to run for three months. Prior to that he had managed the theatre at South Shields for the season there.

Benefit nights were generally held at the end of a season, although I’ve come across a number that occurred for popular actors during a season. On a benefit night, often one of the upper-class patrons from the area would invite his friends and colleagues to attend, with the takings from the house being given to a particular performer in addition to their regular income. According to Wikipedia:

. . . a theatre performer would be hired with a contract typically stipulating at least one benefit performance a year. For this event, the actor's employer, would offer the performer 100% (in the case of a "clear" benefit) of the event's proceeds as a bonus pay. Other forms of the benefit were the "half-clear" benefit in which the actor was entitled to 50% of the proceeds. There were also instances of multiple actors appearing in and benefiting from a single performance.

While the benefit performance was intended to supplement the actor's income, they were also used by theatre companies as an excuse to pay actors a lower salary. The benefit system soon became a strong indicator of an actor's popularity.

No mention of Caroline appears in the newspapers for quite some time. In January 1859 Rochdale Observer announced:

- Saturday 8 January 1859: The Theatre.—This place of amusement was opened on Saturday last, by Mr. J. W. Benson. The opening dramas were, "The Spirit of the Ocean" and “Mary Price," which were very creditably performed. Among the productions of the present week, may be noticed that of "Hamlet," the hero being ably personated by Mr. Benson, “Ophelia" finding an appreciative representative in Miss Elliott. In the after piece, "Bombastes Furioso," Miss Caroline Benson, aged six, created quite a sensation by her sprightly utterance and action. The programme for the ensuing week will be found in our advertising columns.

Caroline made quite a name for herself with her depiction of General Bombastes in the Bombastes Furioso routine. This drama with comic songs was often included in a company’s repertoire; the satirising of popular tragedies was well received by audiences throughout the country. While Caroline was being billed as a six year old, we know from her birth registration that she was actually a nine year old. Perhaps she was small enough for her age to get away with this deception. After all, by now we are beginning to realise that John is a master at disguising the truth when it suits him. For the sake of this tale, we’ll go along with this deception, as all newspaper and advertising media keep this age development going for years.

As her career progressed she became known as the highly talented juvenile actress. Performances that year moved on from Rochdale, north of Manchester, to Elgin, at the northern tip of Scotland, then across to Banff, down to Aberdeen, then by August of that year, she was reviewed in The Glasgow Herald as:

This petite artiste made a most favourable impression on the audience, and her remarkably clever acting evinced an ability for stage playing which, if properly cultivated, may yet raise her to no mean position in theatrical circles. The songs which she sung were highly applauded and encored; and though her voice is as yet but of small compass, there is no doubt it contains the germs of a voice of considerable power.

John and Caroline remained in Glasgow until October. Their next mention in the newspapers comes from The Era, Sunday 22 January 1860; it shows Caroline performing ‘for six nights longer’ at Marylebone Theatre, London. Her performance was in The Heart of a True British Sailor.

The Era was a weekly newspaper for sport, freemasonry and the theatre industry. It listed performances throughout Britain, Scotland and Ireland. From Wikipedia:

Its great features . . . were sport, freemasonry and the theatre. A contemporary observer remarked, "To the latter subject it has always devoted a very large part of its space. In relation indeed to the amount and accuracy of its theatrical intelligence, it far surpasses every other weekly journal. In an 1856 advertisement, The Era claimed to be the "largest Newspaper in the World, containing Sixty-four Columns of closely-printed matter in small type. It is the only Weekly Newspaper combining all the advantages of a first-rate Sporting Journal, with those of a Family Newspaper. Literature and the Metropolitan and Provincial Drama has more space allotted to them in the Era than in any other Journal. The Operatic and Musical Intelligence, Home and Continental, is always most copious and interesting." The Era became regarded as "Invaluable for reviews, news, and general theatrical information and gossip”. Also of value are the assorted advertisements by and for actors and companies.

A month later she was at the Great National Standard Theatre, Shoreditch, playing four characters in Old Heads on Young Shoulders. By the end of that month, her reviews included:

An interlude called “Old Heads on Young Shoulders” ably supported by Mr. H. Lewis, Mr. Bigwood, and Miss Terry, was produced for the opening of a very clever little girl, Miss Caroline Benson, who, in her assumption of a succession of juvenile characters, displayed an amount of precocious ability equal to most of the phenomenon school of children actresses; but when we have said that, taking her age into consideration, and the evident tuition the child has undergone, the performance is clever, we have said all that in strict truth can be advanced on the matter.

John would have spent considerable time and effort into nurturing Caroline’s talent to this point. Not only was she earning high praises; she would also have been contributing considerable money to the family income.

By March, Caroline was still performing at the same theatre, and had included three extra characters in her Old Heads routine. In The Illustrated London News of 3 March, this routine is described as being a little piece designed for the introduction of a little girl of about nine years of age, called Miss Caroline Benson, who enacts several characters very cleverly. We can see that the young actress is inspired a laudable enthusiasm, and gives evidence of real talent.

If we remember that Robert was born in October 1860, Clementine must have been living with Caroline and John by this time. This leads me to wonder if Clementine was the writer behind Old Heads on Young Shoulders . . . I like to think she was! There is an outline of the story in The East London Observer of 3 March 1860:

NATIONAL STANDARD THEATRE. Time which lessens all kinds of charms does not spare those of pantomime. Crowds rush eagerly each day to the promised splendours the great transformation scene amid the frolics of Mr. Merryman, but even these pall after few weeks of the public eye and ear, new attractions are required to draw “bumpers.” At the Standard, “Mary, Mary, Quite Contrary" has not disappeared altogether from the bills, but it has sunk into a subordinate position. The first place is held by a melodrama of the startling and exciting kind—"Holly Bush Hall"—founded on, and very closely following, the Christmas tale in a popular periodical; but the most prominent position is now held by a little lady whom all who love to see freshness talent—natural, unforced dramatis power—in a mere child should not lose the opportunity of visiting. Miss Caroline Benson bears the principal burden of the amusing comedietta of "An Old Head on Young Shoulders"—a piece written for her and fitted to her remarkable abilities. She cannot be more than twelve years of age, yet there is a piquant self-possession about her that would not discredit the oldest stager. She impersonates four members of entire family of Little Pickles, drives by her pranks a gouty old uncle to the verge of madness, and then sooths him by the perfection of blarney to acquiescence in her father's wishes. The changes of dress, voice, and character are rapid and complete, and it is the great merit of Miss Benson in that there are no marks of the stiffness of a child trained mechanically to perform her part, but, as we have hinted, thorough heartiness—an art which marks precocious genius. A character song incidental to the piece receives also full justice from the talented little performer.

I can just see J. W. Benson in the part of the gouty old uncle, with Clementine hustling in the wings to enable the rapid changes of dress required.

These plaudits continued throughout March, bringing praises such as:

. . . and little as juvenile prodigies are generally to be admired it must be owned that Miss Caroline Benson is an exception to the rule. She is not only an intelligent child, but really a budding actress. She has perception of character and cleverness enough to embody it in a satisfactory manner. She appears in the piece successively as an amiable little girl, a noisy, fidgety boy with military tastes, a fat sleepy boy with the appetite of a glutton, and as an absurdly-dressed foppish boy with a love of fast life. In each part she changes her voice, and gives a distinct individuality to the chamfer, so that altogether it may be declared that this little lady exhibits decided histrionic abilities.

At the end of March, the following advertisement appeared in The Era:

Sunday 25 March 1860: TO MANAGERS.-The most accomplished juvenile Actress in the world ONLY NINE YEARS OF AGE. MISS CAROLINE BENSON, having made the greatest hit in London for years, now playing at the Great National Standard Theatre, will be open to form London or Provincial engagements. Her repertoire is varied and extensive, including Tragedy, Comedy, Farce, and Burlesque, with new pieces written expressly for her. This extraordinary child has created the greatest sensation, being enthusiastically received, and nightly called before the curtain. Apply to Mr George Fisher, Dramatic Agent, 22, Broadcourt, Bow. Street, Covent-garden, W.C.

Clan Benson was set to tackle the big-time of theatricals, with a manager to boot!

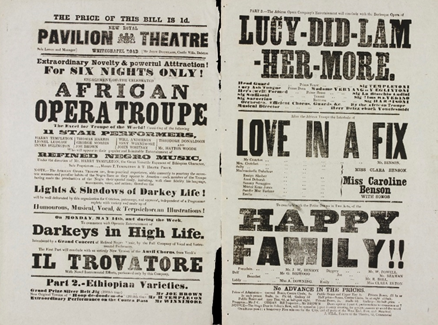

(Note: this playbill came from University of East London Theatre Archives website. That website has since been temporarily deleted. Once it re-appears, I’ll acknowledge the source correctly.)

What a mixed program this playbill displays – African Opera Troupe, a full program of negro music, the anvil chorus from Il Travatore, African burlesque opera Lucy-Did-Lam-Her-More, then Love in a Fix staring Mr Benson as Mr Crochet, Miss Clara Benson in three roles, and Miss Caroline Benson as the six other characters. Mr J. W. Benson then appeared in the two-act drama finale titled Happy Family!!

I think the Miss Clara Benson may have been a misprint; in earlier performances a Miss Clara Elliot often appeared alongside John and Caroline. I have not come across any other references to Clara Benson.

Caroline continued to perform in London through May. By February 1861 they were moving across to Bristol, Wiltshire, Frome and Cheltenham. By the end of May her performances were continuing in Cardiff; here they were not as well received as previously. They would not have been pleased with the two following reviews:

Cardiff Times - Friday 24 May 1861: Miss Caroline Benson, only nine years of age, the accomplished juvenile mimic actress, vocalist, and dancer, who had announced that she would give her elegant and amusing drawing-room entertainment at the Castle Hotel, in this town, on Thursday, Friday, and Saturday last, came here, but we are sorry to say that on the three nights she did not take as much money as would pay the expenses.

Merthyr Telegraph, and General Advertiser for the Iron Districts of South Wales - Saturday 25 May 1861: DRAWING ROOM PHENOMENON.—Whatever brought the clever child Caroline Benson with her precocious and aristocratic patronage into this quarter of the world? We have no time after performing our three great functions of love, war, and drinking, to be amused by a child's clever scenic trickeries, especially with a two shilling ticket thrust in our faces. If there be people so soft as to pay 2s. for such an entertainment, we cannot object to it any more than the sailor's lighting his pipe with a five pound note, or to Cleopatra drinking pearls in her wine, but the first is decidedly the most absurd, because he throws away time as well as money, and he sits his two hours in a sweltering small room, quite as great though not so amusing an exhibition as the forward young puss he went to patronise.

Come August they are on the move again, from London, to Luton, and Wolverton throughout that month. A rather lengthy piece in newspapers from Northampton and Luton takes us right into the program offered:

— On Wednesday evening last a small but select, audience was present at an entertainment at the Mechanics' Institution, which, by its variety of character and able performance, afforded a treat such as is rarely given in this neighbourhood. We allude to the artistic entertainment of Miss Caroline Benson, a young lady of nine years of age, who, by great natural ability and the most careful training, permeates many characters in manner true the life. The little drama was "Little Annie's Birthday," which she takes successively the characters of Annie and the little lady and gentleman visitors who come wish her many happy returns; Mr. and Mrs. Benson taking the sustaining parts, the former in the character of an "old servant," and the latter in that " Annie's Aunt." Several appropriate songs are sung by Miss B. in the various characters assumed. This is followed by a well-written piece entitled "A Son by Advertisement." in which Mr. B. appears as a disconsolate old bachelor, who, as a last resource against utter wretchedness, is led to advertise for a son that shall be a solace to him his declining years. Here Miss Benson assumes the characters of the applicants, who present themselves the persons of a "very boyish young Lady," who almost kills the old gentleman by showing no consideration for his gouty foot. A "Young Rifle Volunteer," who levels his piece at the old gentleman's head, and horrifies him almost out of his wits. This character is excellently rendered by Miss Benson; the tang so fashionable now a days, and the affected manner of the rising generation, she most piquantly imitates. Then follows the youth who is ultimately adopted, who pleases the old gentleman greatly, and who turns out to be an orphan, the son of a young woman whose husband's death broke her heart, and who was the first though cruel love of the old bachelor himself. An "Irish Girl” also applies, in company with her mother, Mrs. Biddy Macarthy (Mrs. Benson) In the character of the young lady of 62, who proposes to the old gentleman, arguing that it more natural to adopt a wife than a son, Miss B. is inimitable. The dancing of Miss B. the characteristic dances of Ireland and Scotland is very faithful. Her singing is artistic, but, owing to the straining of her voice the personifying of characters, her voice sometimes rough and stubborn. The performance, as whole, is most admirable, and, for girl her age, wonderful.

1861 and 1862 saw Caroline starring in performances from London to Scotland. In July 1863 a new performer appeared with our pair; I assume that this is around the time Clementine and John separated. Miss Emma Hedgethorn now has a place in their shows. One newspaper article refers to Emma as being the niece of Mr. J. W. Benson, although in our 1861 Census for this family she is nominated as a servant. She remained as part of the trio until the end of 1865; perhaps she then married, as no further trace of that name can be found.

On 8 May 1869 Caroline Matilda Benson Whitehead married Thomas Clapham – her father was recorded as John Benson Whitehead, artist, 14 Belgrave Street, Leeds. Thomas was a mercantile clerk. The marriage took place at St John the Evangelist, Leeds, Yorkshire.

Five months later, the following notice appeared in The Era:

- Sunday 17 October 1869: MISS CAROLINE BENSON begs to inform All Managers that she will not be at Liberty to accept Engagements until the 5th January, 1870, after which date she will be most happy to arrange with a responsible Manager for Juvenile Lead and Light Comedy 5, Brunswick-place, Bradford.

Caroline was very possibly pregnant at this time, as the 1871 Census shows that she and Thomas have a one year old child, Edith. Also living with them were Caroline Whitehead, mother-in-law to Thomas, and John Whitehead, brother-in-law. Caroline senior was age 39, widow, annuant, born Wolverhampton. John was age 15, commercial clerk born Durham, South Shields. They were living at 40 Edinburgh Street, Bradford.

Her husband John had died in 1870, but if he and Caroline had been formally married, then his marriage to Clementine Enoch was most questionable!

By the 1881 Census, the family were now at 73 Ewart Street Bradford. Edith (age 11) had been joined by Henry (age 9), Gertrude (age 8), William (age 4), Sarah (age 3), and John (age 2 months). In that 10 years, Caroline senior had aged considerably – she was now 59 years old, and was described as being formerly Theatrical Manager’s wife, born Wolverhampton.

Between 1876 and 1881 Caroline was still doing some acting – goodness knows how she found the time! After then there are no further notices that include her name.

I can’t find a record for her in the 1891 Census; in fact, the next record is an extremely sad one. Her death certificate shows that on 3 August 1906 Caroline Clapham age 56 years died at Horton Workhouse, from alcoholism and Lyncopse (hardening of the arteries around the heart). She was the widow of Thomas Clapham, a General Labourer of 1 Arthur Street, Bradford. The certificate was signed by F. A. Crane, Matron.

To be a resident in the Workhouse, a person would have no family able to support them. While the local parish would feed and clothe these people, the living conditions were very meagre, and residents were expected to perform work tasks to help defray those costs. What a tragic end for one who had risen to such performing heights.

MR. J. W. BENSON

Now, time to return to our main character, Mr. J. W. Benson. I’ve found this saga most difficult to piece together in a logical sequence that doesn’t jump around too much. His many wives, many name changes, and many places of residence and performance are such a juggling act. I waver between deciding he was a devious, deceitful person, to admiring him for being able to turn his hand to so many talents. Perhaps the truth lies somewhere between these two extremes.

John always maintained on official documents that he was born in Knaresborough, Yorkshire, and the dates given correspond to him having been born around 1808–1810. Keeping in mind that census and other data were taken at different months throughout the year, and ages were rounded rather than stating a number of years and months, it's difficult to be completely accurate. So to find a birth date was an important base to begin.

Knaresborough is a district 16 miles to the west of York. Immediately to the north of Knaresborough lies the village of Farnham. Looking at newspapers of the time, Farnham was a farming community. Colonel Robert Harvey was the local landowner who led the Knaresborough Volunteer Yeomanry Cavalry.

I can find no record of a John Whitehead being born in that area around this time, but there is a John Benson who was baptised on 10 September 1809 at Farnham. These details are listed on the familysearch website. That family also had sons Samuel (1805), and Joseph (1807).

This is the only likely record of his birth that I can uncover. His use of the surname Whitehead later in his life is still a mystery; did his family suffer hard times and need to hand their child over to be raised by friends or relatives, or was he taken under the wing of another influential adult with this surname. There were Whitehead families living in Knaresborough in census records for 1841 & 1851. Prior to those dates, individual names were not listed. Perhaps in the future this piece of the puzzle will be solved.

John also used the occupation comedian on most of his official record papers. By this, I assumed that he would have been one of those slap-stick characters who were popular in theatres at that time, often used to in a performance of light entertainment style shows.

However, in the newspapers of the early 1800s a serious actor is often described as being a comedian, more in the definition of a serious player rather than a funny character. A theatre manager would have a troupe of comedians he toured with, offering performances that consisted of Shakespearian plays as well as light variety.

Before we get involved with John’s acting career, I think it best to tackle the relationships he had with a number of women. These ladies appear at regular intervals throughout his life; first Hannah, then Jane, then Mary Ann, then Caroline, then Clementine – and possibly one other as yet unidentified by name. These six women occasionally overlapped; it would be most interesting to know who, other than John himself, knew of the existence of all of them!

The first reference to John as an actor is from the Lancaster Gazette - Saturday 25 September 1830, under death notices: Hannah, wife of Mr. John Benson Whitehead, comedian, aged 29.

There is a record of a John Benson marrying Hannah Tishe (or Tike), on 11 February 1830, at Tickhill, York. Tickhill Farm is 2.2 miles to the south east of Knaresborough on current roads, so while this is the most likely possibility available, it is by no means conclusive. No formal registration of Hannah’s death has come to light as yet.

John had been in that area at this time, playing the part of Salarino in The Merchant of Venice, and Henry VI at the New Theatre, Kendal. These performances continued to be advertised from mid-July to early September 1830. Provincial theatres such as this one tended to have their performances in ‘seasons’, generally running through the summer months, then again for a shorter season leading up to Christmas time.

At this stage of his career, he was named as Mr Benson. However, this is where the first of the little twists in John’s life occurs. On 7 February 1833 John Whitehead married Jane Roxby Beverley at Tynemouth Christ Church, North Shields, Northumberland. John was nominated as a widower. The witnesses to this ceremony were William Roxby Beverley and Samuel Roxby. You could be forgiven for assuming that this is not our man, but when Jane died some years later, the death notices in newspapers were as follows:

Hampshire Advertiser - Saturday 28 October 1848 - On the 27th instant, at Lansdowne-hill, Southampton, the wife of Mr. J. W. Benson, tragedian.

Leeds Intelligencer - Saturday 4 November 1848 - Southampton—On the 27th October, after a long and painful illness, the wife of J. W. Benson, Esq., daughter W. R. Beverley, Esq, formerly Covent-Garden theatre, and sister of William Beverley, Esq., the celebrated scene-painter, and of the present lessee of the Scarbro', Durham, Sunderland, and Shields theatres.

In neither case was the poor woman given a name of her own. We need to remember that in these times a woman was considered to belong to her husband, with all her possessions at marriage becoming his property.

My investigations of the Beverley/Roxby family have shown that the Roxby family originated in Hull, and added the Beverley title to their acting surnames as this is the part of Hull they had lived. Yet another example of the freedom with which the acting community played with names as it suited them. William Roxby Beverley was the patriarch, manager and owner of provincial theatres for some decades throughout central England. He also had a son William who became renowned for his spectacular scenery for these shows, and oil and watercolour paintings. On 21 November 1800 Jane had been baptised at Saint Martin in the Fields, Westminster, London. She was the daughter of William & Mary Beverly. I have not come across any children from her marriage to John.

So from these details, I am comfortable that our John is this man. Jane’s death certificate notes that John was present at her death, at 3 Lansdown-Hill, Southampton. He was acting at the Theatre Royal, Southampton at this time.

John had married Mary Ann Tyrer Parish on 18th November 1840 at Bradford, York. He gives his occupation as Bookkeeper, widower, with father William Benson being a Watch Maker. Mary Ann is a spinster, daughter of Edward Parish, Traveller. Both were of full age. Both lived in Bradford at this time. The details of father and career for John don’t tally with those on other official documents.

It would be easy to conclude that this isn’t our John Benson, were it not for the newspaper marriage notices for that date. Three papers in the Yorkshire, Leeds and Sheffield areas carried similar entries:

MARRIAGES. Yesterday, at Bradford’s parish church, by special licence, Mr. John Benson, comedian, to Miss Mary Anne Parish, daughter of Mr Edward Parish, for many years proprietor of the largest portable theatre in England.

Special licence was probably because they hadn’t been resident in the parish for the required three weeks’ notice for the banns to be read in church. In such cases, the minister could grant special dispensation for the marriage to proceed.

So here’s a little complication. John married Jane in 1830. John married Mary Ann in 1840. Yet John was present at Jane’s death in 1848. Does this mean that Mary Ann had died sometime between 1840 and 1848; had John then returned to his wife Jane? As I can’t find a likely record of Mary Ann’s death (their constantly being on the move makes this very tricky), this just becomes one of the puzzle pieces that are yet to be uncovered.

After Jane died, John next has a relationship with Caroline Robinson. In 1850 their first child Caroline Matilda was born; we have already studied her career. Their second child John William was born in 1855, at South Shields. On both birth certificates, the mother was identified as Caroline nee Robinson. I cannot find a marriage record for John and Caroline, so perhaps this was a relationship that was never formalised in the church.

We know that Caroline snr was living with her daughter’s family in the UK censuses of 1871 and 1881. After that time her trail disappears, but she was definitely alive long after the date of John’s next marriage to our Clementine in 1860.

After John and Clementine separated sometime early in the 1860s, he doesn’t seem to have re-married. But (there’s always a but with him), following his death in April 1870, a number of items appeared in the newspapers regarding the details of this event. It would seem that someone had written to The Era newspaper, enquiring to his whereabouts. Newspapers in those days often had written replies to questions, but the original query was never printed. The following appeared in The Era on each Sunday in February, 1871:

The Era - Sunday 5 February 1871: F. A. (Edinburgh) – Inquiry shall be made. We have no record of the event.

The Era - Sunday 12 February 1871: F. A. (Edinburgh).- We have no record of the death of Mr. J. W. Benson, once a Manager of Theatres in the North of England. He is said to have expired in London during the summer of last year. Perhaps some of our readers can supply the information sought.

The Era - Sunday 19 February 1871: EDITOR. - Sir, - in answer to your Edinburgh correspondent, I have to inform you that my poor father died at Downham Market, Norfolk, last Spring. Hoping you will kindly insert this in your next issue, I remain, yours truly, CAROLINE BENSON CLAPHAM 10, Edinburgh-street, Lesterhills, near Bradford, Yorkshire.

The Era - Sunday 19 February 1871: THE EDITOR.-Sir,- For the information of one of your correspondents, I beg to state that the late J. W. Benson died March 28th, 1870, at Downham, in Norfolk, from a severe cold caught in a vault in the theatre, which was designated as a dressing-room. He was buried by public subscription in that town, the good folks of Downham, behaving in a noble manner upon the occasion. Yours truly, CHAS. LERIGO, Prince of Wales Theatre, Wolverhampton.

The Era - Sunday 26 February 1871: MR.EDITOR.-Sir,-With regard to Mr. J. W. Benson's death, allow me to remark; as Lessee of the Downham Theatre, that Mr Benson died from disease of the heart, from which he had long been suffering when he joined my company. His health was then much broken, and, doubtless, a severe cold he contracted accelerated his death. I think the statement of Mr Lerigo (my then leading man), to the effect that Mr B. was buried by public subscriptions, uncalled for, and calculated to wound the feelings of his family and friends, besides not being strictly true, as I gave his widow the proceeds of a half clear benefit and a small sum towards funeral expenses. Besides this, she had material assistance from many of his friends and relatives, and was therefore in no need of the subscription that "the good folks of Downham" so generously contributed. I may add that the dressing-rooms, though very bad, were little worse than these whence Mr B, last hailed from, and that the verdict at the inquest corresponded with the medical evidence, viz., disease of the heart. Apologising for so far troubling you, I am, Sir, your obedient servant, SAMUEL GEARY.

John’s death certificate states that the cause of death was a “Visitation of God’ – just adds one more layer of drama to his story, doesn’t it!

I had always assumed that Clementine was the instigator of the original enquiry, with F. A. of Edinburgh being a person acting on her behalf. At this time Clementine and Robert were living in Edinburgh. A few months after John’s death details were published in February 1871, Clementine married Frederick Montagu Watkins, in June of that year.

So . . . if Clementine wasn’t the wife referred to in the statement above I gave his widow the proceeds of a half clear benefit and a small sum towards funeral expenses, then who was this next wife? Once again, it’s proved to be a fruitless task searching for a possible marriage of John Benson, or John Whitehead, to some unknown woman, in any of a number of towns in Britain. Another mystery puzzle piece to be completed at a future time.

In case you lost count during that lengthy process, there were possibly six women who had shared a segment of John’s nomadic life!