Timeline 2

This edition

This edition Timeline: Analog Two is published by Enriched Books and Tablo. It is the second in a series designed for students of film and television and small screens everywhere. This update continues revisions, corrections and an added interview with former Lucasfilm Computer Division CEO, Robert (Bob) Doris.

The right of John Buck to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patent Act, 1988. Any unauthorized distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly. Besides it’s uncool to copy.

I have made recorded contact with all known copyright owners. Email me if you wish to make corrections. Copyright John Buck 2015

10. Xerox

TRACE AND 409

David (Dave) Bargen had worked at CMX Systems for its entire lifespan but decided to leave with the Orrox acquisition.

I continued to write software and worked as a consultant for Vidtronics alongside Jack Calaway who was the Engineering Manager. We developed a close working relationship.

TAV engineer Tom Werner recalls one of video’s most significant partnerships:

Of course Jack was my best friend but at one time he was also my boss. Dave was a magic man. I remember looking on in awe as Dave would make a hand patch into the CMX system computer via the switch register, and thus solve some pesky problem. Jack and Dave became extremely good friends as well as a consequence of those early efforts.

Jack and Dave collaborated a fair amount on the original CMX 300 keyboard layout and choices of key colors.

Bargen and Calaway were looking to solve the principal flaw in the workflow of electronic editing. The computer editing systems used for offline work had no internal list management. At the end of the editing session, there were many more edits than were actually in the sequence.

It became known affectionately as a ‘dirty list’ (above) and Calaway identified it as problematic to editing system development. Bargen recalls:

Jack Calaway saw the need and encouraged me to write a program to fix the problem. I called it the List Cleaner. At the time many video monitors didn't have anti-static coatings and there were no restrictions on people smoking indoors and inside editing bays. Monitors got dirty fast and needed to be cleaned, much like the editing lists.

Jack didn't like the name List Cleaner, he told me that it should be called 409, after the Clorox cleaning solution Formula 409 which he liked to use for cleaning TV and computer monitors. The name stuck.

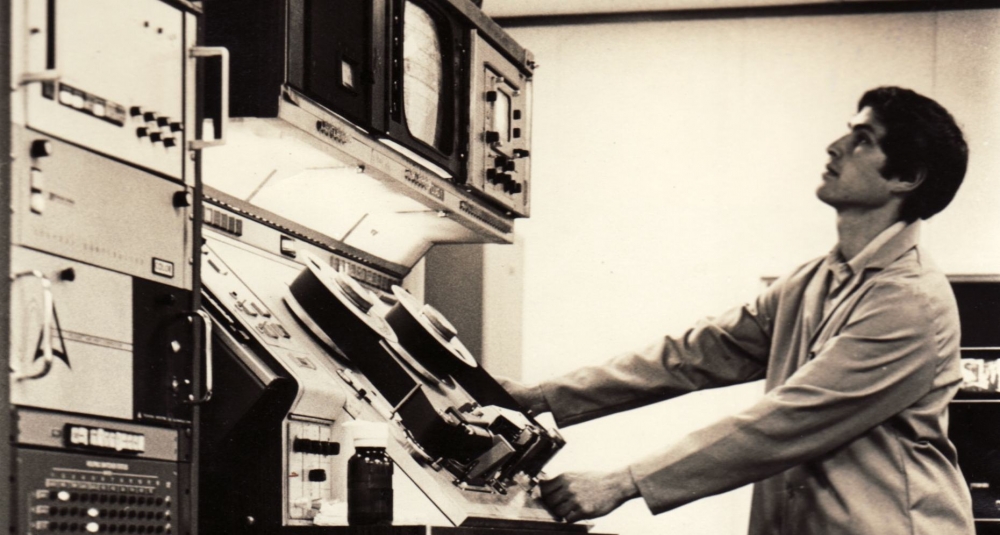

Bargen's 409 software program took the raw edit list and eliminated all the extra edits. A ‘dirty’ list was fed into the computer (above) and hitting ‘C’ for Clean started the 409 program. Bargen’s program eliminated any overlaps in edit ‘out’ points and also joined any consecutive audio or video edits that came from the same source by hitting ‘J’ for Join.

If an editor wanted to do it in one keystroke they hit ‘A’ for All. With the editing decisions cleaned the sequence could be exported to a paper tape or floppy disk to be fed into an online system. (below)

Bargen also identified and subsequently solved another problem caused by linear recording of events on videotape. Any time an editor wanted to make a change to a linear edit recording, all the information after the changed event had to be re-recorded back onto the analogue videotape.

As a ‘work around’ video editors prepared a first cut, then used this first cut and not the original rushes as a source reel to tighten the show.

Unfortunately by doing it this way the time code and reel number for the source material was lost. Bargen developed another program called Trace that took each edit in a sub EDL and traced it back to find the original reel number and time code. Bargen continues:

Jack and the Vidtronics editing staff did extensive testing to be sure that the programs met the needs of professional editors.7

Although the work had been collaboration between Bargen, Calaway and the Vidtronics team, it was Bargen who won the Emmy for Outstanding Achievement in Engineering Development for his work in developing the two breakthrough computer programs.

LARRY SEEHORN AND TVA

Larry Seehorn continued experimenting with editing software and sought out the advice of former HP colleagues like Steve Wozniak:

I was working at HP at the time (and) I ran into Larry Seehorn when I was looking for a video editing system to purchase. I purchased a U-matic ¾” tape editing system which I loved. It brings back better memories than any of today's digital editing equipment. I guess that's how it goes. The crude old stuff was more fun. I loved lining up scenes with dials on two monitors, and then putting an edit into effect and waiting until it completed. Larry presented me the concept of designing a SMPTE decoder. I was stunned to learn of this time code being added to 1" video equipment, the professional equipment of the time. It was very logical to including a timing track along with the video. As I recall, the audio track contained this time code, frame by frame. I was surprised at how long the whole code was, down to the frame number. I seem to recall some interesting issue between 29 and 30 frames. I did design a circuit to decode the SMPTE code coming off the tape. My SMPTE time code reader design was based on synchronous counter.

My design was purely digital. It did not have any sort of analog filters to deal with the varying data speed. I just assumed that the signal that reached me had already gone through that circuitry and was pure and correct (edges from 0 to 1 and 1 to 0 were accurate, time-wise). Back then I did continual design jobs for friends and acquaintances on my own time. This job, like almost all of them, was probably for free. I just loved using my design skills for anything. It was my most fun thing in life. At the time I was very surprised to learn about this new SMPTE code.

Ralph Conradt also recalls:

One of Larry's code writers was a very creative bearded individual who one day said that he no longer could work on the editor, but asked Larry if he would like to invest $1000 in a start-up he was creating with another former HP employee. Larry said he had no extra money so the young man sold his own HP calculator.

As Wozniak contemplated leaving HP, Steve Michelson (below) returned to California from Australia where he had trained as a 2" tape editor at television station TCN 9 Sydney under Australia’s premier video editor Steven Priest. He recalls:

With Editec, one could select a spot on the Master tape and consistently cut on that spot; but the slave had to be back cued and that wasn’t very precise. Priest had figured out a system using masking tape and the 360 degrees of the circular tape reel to create a low-tech manual system to execute frame accurate repeatable edits. The math and science was one thing, but the art of execution during the heat of an edit session with an air deadline an hour away was quite another thing. The skills I learned at TCN9 would serve me well in the future.

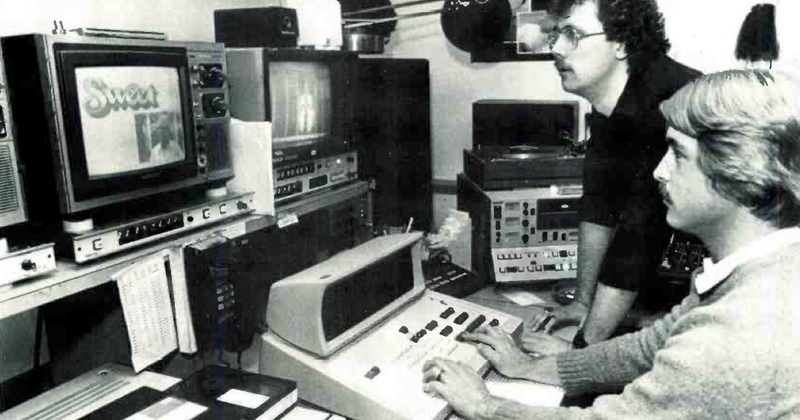

Michelson landed a job as an editor at TVA (below).

In typical fashion Larry Seehorn threw me into a session on my first day, giving new meaning to the term “baptism by fire”. Larry called me ‘Stevie One Pass’ because I tried to get all the machines rolling together and record a finished sequence without the need for additional copies or passes of the videotape machines. Nothing was repeatable and most everything was surprising during this process. The people I enlisted to press buttons, switch key cards, add VO, make level adjustments on the fly and a dozen other things had no idea what the finished piece would look like. Every time the sequence was over they all rushed to the edit room to see how it turned out

The ‘One Pass’ name lived on in electronic editing.

Meanwhile Loran Kary was looking for work after studying Fine Arts and he too landed a job at TVA.

The more I worked there, the more I learnt about post-production. I became fascinated with that, so when the opportunity arose I applied for a different position at the company as an editor, starting off in duplication working with Larry. Like everyone at TVA, you would be taught the video end of things, and they would train you up, leading into editing. For three years I was a video editor. At the same time I was studying electrical engineering at a local college at night because once I started working as an editor surrounded by all this electrical equipment it made sense to know how it all worked. I took the whole curriculum and learnt everything starting with analog to digital to learning how to program microprocessors. Meanwhile on the side Larry was still developing his computer editing system.

Michelson and Kary became key players in the evolution of electronic editing but for the moment they watched as Larry Seehorn tried re-invent video editing. Michelson recalls:

Even though there were computer-editing systems already available from companies like CMX, Larry felt he could make a better mousetrap. In the evenings at TVA, Larry would roll out his latest invention, the EPIC. It was designed to be a more editor friendly system than the CMX systems of the time. At first it looked like a patient in intensive care. Hand wired and in need of real machines and operators to test-drive and critique. The system arrived on a cart, it disabled the shuttle drive and could seek and find a frame in seconds using time Code.

Seehorn himself explained later:

When film editors speak fondly of the feel of cutting film, what they're describing is the immediacy of the thing. Make the edit, put it back in the sprockets, and view it.

Seehorn's perspective was visionary. It wasn't going to be good enough that electronic editing simply replaced the medium of film with video. The digital Moviola had to be better than Serrurier's original system, and Seehorn spent much of his entire career trying to make that so. Steve Michelson adds:

The collaboration between editors and engineers was inspiring and as a group we developed technical solutions to serve creative ideas. It put Larry at the forefront of the editing world.

TVA colleague Ralph Conradt recalls:

During these early days I was one of the test editors, providing feedback on ease of operations and intuitiveness. Even when CMX/Orrox released a new CMX system, Larry was not daunted. To him CMX was a hardware only system and what he wanted to create a device was a software based system that users could program, using hot keys to personalise the system.

Seehorn worked with programmer Kevin Fitzgibbons to focus on the software design for the EPIC editing prototype. He wanted the new system to be a multi-machine editor that could handle any format tape machine, and have operating capabilities that could be customised by the editor himself. Loran Kary recalls the continuing work:

Larry and Kevin had developed a user interface that was much more efficient and intuitive than other online systems. Of course it had a lot of the same features as the CMX systems but it did it more efficiently. Editors who spend all their days hitting keys and trying to make things happen quickly really appreciated the way Larry had configured the system to work.

The EPIC software system ran on a Data General Nova computer and its abilities grew to include a full complement of VTR and switcher control functions. Steve Schwartz recalls another attribute of the EPIC that was borrowed from its HP roots.

Larry Seehorn's new system used the logic of a famous Polish inventor Jan Lukasiewicz. In the 1920’s Lukasiewicz developed a formal logic system which allowed mathematical expressions to be specified without parentheses by placing the operators before (prefix notation) or after (postfix notation) the operands.

For example the (infix notation) expression

(4 + 5) × 6

could be expressed in prefix notation as

× 6 + 4 5 or × + 4 5 6

and could be expressed in postfix notation as

4 5 + 6 × or 6 4 5 + ×

Prefix notation also came to be known as Polish Notation in honor of Lukasiewicz. HP adjusted the postfix notation for a calculator keyboard, added a stack to hold the operands and functions to reorder the stack, and then dubbed the result Reverse Polish Notation (RPN) also in honor of Lukasiewicz. Schwartz recalls:

Larry Seehorn was of course an HP alumni and he realized that Reverse Polish Notation (RPN) was very efficient. People may remember that his EPIC had a look ahead editing function and a nice timecode reader, which worked a little better than the others, but what was great about the EPIC for an editor was how Larry allowed the editor to cut down on the unnecessary key strokes of the CMX. So instead of trim mode one enter, it was one trim in. It saved a key stroke, you actually saved 100's of keystrokes which meant you could edit so much faster and more efficiently with the EPIC. You could just jam.

Seehorn knew from his experience of video production at TVA, and computing with HP, that a genuine change in electronic editing could not occur until the post-production process was free of analog’s problems and became digital. Only then could it be nonlinear, and truly rival film editing systems.

VIDEOTAPE IS HERE

Around this time the two-man team that exploited the Sony U-matic deck beyond its inventor's boundaries came together at editing equipment maker TRI. Gary Beeson joined Dennis Christensen as TRI continued to sell the EA3, EA5 and EA6 Editing Automators that controlled 1” helical scan open reel tape machines in offline editing suites. The two men had seen IVC and Datatron ignore the opportunity offered by the initial U-matic VTR but with the release of Sony’s new VO-2850 U-matic Beeson and Christensen hoped that TRI could embrace the cassette or 'captive reel’ machines. Christensen recalls telling TRI’s founder Bob Cezar:

"We’ve got to develop an interface for the Sony VO-2850 that allows us continuously variable tape motion control” And he said: "No, that (Sony) machine is a piece of junk. It’s a consumer machine, it’s not professional, we don’t want to be associated with it because it will sully our professional reputation" and I said “Well you might see it as sullying our professional reputation but I see it as quadrupling our sales”.

Gary Beeson recalls:

It was obvious to us that there was a need to be able to use film style editing techniques with the new Sony VO-2850 machines with their 'captive' reel but Cezar said “we had to stay with the open reel format and stay the course”. We were talking to distributors every day and we could see the way the market was moving.

The two men decided to follow the converging market of video and technology as Los Angeles was buzzing with technological change. Robert (Bob) Seidenglanz had worked as an engineer at Hollywood Video Center but when his employers had refused requests to embrace smaller recording devices for shooting, Seidenglanz started his own company Compact Video. He told Billboard magazine:

Videotape is here. Now. This is the future as more and more producers are beginning to find out. 1

Seidenglanz wanted to adopt the latest editing technologies available. Tom Werner recalls:

Compact's engineers Joe Sayovitz and Gary Matz pioneered the use of intelligent interfaces in editing. They used some easily available minicomputers from companies like Ramer Industries in the San Fernando Valley, each dedicated to an Ampex VTR. Compact Video made much of its very proprietary editing system and many in the LA area were deeply impressed by their effort.

Seidenglanz became a proponent of electronic editing in the years ahead. Meanwhile Bernie Laramie settled in Culver City.

Bob Kiger, Dick Sebast and I formed the Videography Company of California as LA's first commercial production company specializing in single camera videotape originated commercials that 'look like film'. It didn't take long to realize that we needed a better way to edit.

Tom Werner had worked at Las Vegas TV stations KLAS and KVVU before settling into post-production house Trans American Video in Hollywood. He recalls:

Videoography was one of the first companies to embrace video offline/online. The early attempts at doing "paper edits" using either IVC 1" or U-matic had much more difficult assemblies, partly because the early U-matic machines could not freeze a frame. There was much confusion with timecode calculations especially when non drop or drop frame timecodes were used, or the especially dreaded mixed timecode situation.

Kiger and his colleagues used Trans American Video’s editing suite. Laramie continues:

TAV married a Datatron Vidicue editing console with two IVC 1" recorders and created an offline-editing suite. Because it was not yet computerized, we had to manually create our EDL for automatic Assembly on the CMX Edipro-300 with the original 2" tapes.

Werner adds:

I remember Bob Kiger running to the toilet to vomit because we did an auto-assembly of a program on a tight schedule for a particularly fussy client and there were black holes at some of the edit points. Turned out there was some confusion as to whether to log the record in times or the play out times, This could lead to unexpected results which had to laboriously repaired. We all survived, but it was hardly a low tension "automatic assembly".

Laramie continues:

We also conducted the first non-linear automatic Assembly when it cut a four camera "Barney Miller" episode one reel at a time. In effect we had thirty minutes of coded black, which was checker-boarded, edited until all four isolated tapes were processed. The end result was a finished show cut in less than 3 hours without the need to constantly change and re-thread 2” tapes. This was a HUGE saving in time and money.

Werner continues:

There were other problems as well. As production values steadily increased, the expectation of what could be achieved in post production did so too. Thus there were color correction, optical effects and lots of audio repairs to do on line. Everybody wanted to minimize the expensive on line time at the post house and those "far off-line" efforts often only sufficed for a pre-edit.

Having proven the value of the Offline to Online workflow, Videography bought a Datatron Vidicue system. Bernie Laramie recalls:

The damn thing didn't work very well, but I became enamored and used it to cut a few of the ABC ‘After school’ Specials like ‘Psst Hammerman's After You’.

It was the first network drama program to be edited and delivered on videotape. Meanwhile Dennis Christensen and Gary Beeson believed the key to success for makers of editing equipment was to ignore 2" and 1" videotape recorder technology and begin interfacing controllers for Sony's ¾” tape decks. TRI management disagreed and the two men quit to form their own company as Christensen recalls:

We were driving down the Bay Shore freeway through Silicon Valley trying to decide what to do next and we knew that the U-matic cassette was the key. The VO-2850 was something that could bridge the gap into professional television newsgathering. I said to Gary, “We should build our own edit control device and make an interface for the Sony VO-2850 and put something like a joystick on it, so that you can have a much better human interface. The buttons on Sony's editing device are a terrible ergonomic mess. They don’t want to have to look down to see what button to press, they want to keep their mind on the screen thinking about telling a story. The editing control device needs to be as transparent as possible. We have to create a more user-friendly human interface, because that’s what editors need. ”

CONVERGENCE

The two men had a plan but no company name. Christensen recalls:

We noodled around for a company name. We were converging the technical potential of the world of electronics and videotape with the artistic skill of film editors, so after five minutes it seemed obvious to me, Convergence Corporation.

Within two weeks, they had started building a prototype as Beeson recalls:

The main aim was to create a new product specifically for the VO-2850 deck, to create a video editing system that acted and felt like a Moviola. It would let film editors treat video just like film. They didn't need to learn any new techniques. It wasn't a system like the Sony RM-400 or some big computer controlled system like a CMX editor. Those systems were confusing and editors didn't want that.

Christensen recalls:

Beeson stayed at my house in Orange County and we started building an editing controller in my garage. I bent the sheet metal and went out and bought some push buttons and Beeson was designing circuit boards.

Gary Beeson worked on an interface for the Convergence editing device to sit between the ¾” replay decks and recorder. He had to converge modern electronics and analog machine control technology yet retain the simplicity of their editing benchmark, the Moviola. Dennis Christensen was in regular communication with potential re-sellers and a potential first client. If CBS Television in New York approved their system, Convergence Corporation could become successful overnight but there were problems to overcome. As a result of being designed as a home video recorder the Sony VO-2850 was restricted in how it could play videotape. In short, it couldn't function like a Moviola.

CBS was anxious to utilize what we were working on if we could deliver it but they had close relationships with Sony and Sony said it was impossible. Sony's engineers told CBS that an editor could never reverse or back tape up on the VO-2850 and you could never run it at continuously variable speeds for slow motion. To which we said ‘Well that’s your opinion, we’re going to do it’. Pretty soon we had a working prototype of the first ECS-1 editing control system with dual joysticks on the front of it. Reversing tape and playing slow motion speeds, continuously.

RADY AND THOR

Others involved in editing’s future moved. Bruce Rady graduated from the University of Kentucky in 1975 and began work at the prestigous Bell and Howell Company in Chicago. Rady worked with Delmar Johnson, John Flint, Thomas Wells and Rolf Erikson to refine microfilm image reading devices and bar code readers. It prepared him for a career dealing with image access and manipulation. At another of America’s blue chip engineering companies engineers Dick Hathaway, Ray Ravizza, Jim Wheeler and Don MacLeod worked on a new professional helical VTR for Ampex, codenamed Thor 2. They hoped it could be used to playback the thousands of existing A format videotapes. Jim Wheeler recalls:

As Dale Dolby put it, "There are 30,000 ‘A’ machines out there and that means there are 30,000 formats". The old Ampex "A" machines were terrible for interchange! I was asked to analyze the "A" format interchange problem and I concluded that it was complex and involved the scanner surface finish, capstan, the movable guides and the weak top plate. That's when Dick Hathaway, a genius mechanical engineer came up with a solution for the capstan, guides and top plate.

Ampex VP Mark Sanders recalls:

They had started from scratch, with a blank sheet of paper in a lab. Their aim was to have no more moving guides and a base plate that would be comfortable on a locomotive.

Wheeler continues:

Dick conceived of the scan tracking method while driving on an Interstate highway on vacation. When he got back to Ampex, he called me into his office and asked me to experiment with piezo-electric material to see if we could fasten a head on a beam and make it move at least one video track.

Sanders adds:

Hathaway came up with a brilliant scheme to move the video head within the scanner. Ray Ravizza developed the sophisticated servo systems to allow the head to follow the predicted tape track. The system worked amazingly well.

Wheeler recalls:

Then I came up with a solution for the scanner problem.

Mark Sanders recalls:

There was now a way for broadcasters and users to recover (play) the hundreds and thousands of helical scan videotapes that had been recorded previously and left to gather dust. We called it AST (automatic scan tracking) and it was God’s gift to helical recording.

The team came upon an unexpected discovery that won them an Emmy. Sanders continues:

If you stop a Quad machine at any time without retracting the heads from contacting the videotape, it cuts the tape in half. If you do the same thing with a helical machine you still see a picture with a noise bar from the head not tracking the tape properly. Importantly in helical machines the tape rides on a air cushion and it doesn’t cut the tape. The new Thor head 'sniffer' head stayed on track even when the machine was stopped. Right there in front of us was a perfect still frame picture without the noise bar!! Then we moved the tape slowly and it played back as perfect slow motion. There was a definite, 'Hey wait a minute we never thought of this."

Almost by accident the team had solved the quandary that had evaded many before them. The Thor 2 machine was able to offer affordable reliable slow-motion to producers who felt restricted by expensive disk drive recorders like the Ampex HS-100. It also had unique opportunities for editing.

You could 'rock and roll' the tape back and forth and actually watch the picture. That darned machine would stay perfectly on track, no matter how one gyrated the tape and no more noise bar.

As the Thor group fine tuned their work, the two young businessmen who had quit their jobs to create an editing system stood inside a small display stand at NAB. Dennis Christensen recalls the debut of the ECS-1.

We went to NAB in March of ’75, a year after we quit TRI and there were lines literally 100ft long waiting to get into our little booth. They saw what we had and it was so obvious to people that the Convergence editing control device was light years ahead of anything else on the market. Electronic newsgathering was becoming a big deal as the stations converted from film to video. Sony’s RM-400 was the only editing device on the market that they could use that was economical, otherwise you had to spend $50-100,000 dollars for a CMX system not including tape machines. Even if you afford one, you couldn’t put a CMX into a news suite.

What most editors who visited the Convergence booth remember about the ECS-1 was its interface. The unit had dual joystick controls for controlling forward and reverse motion, to select and adjust edit points on both the playback and record VTRs. Tape speed in both directions ranged from a still frame up to three times normal playback speed Gary Beeson recalls the debut:

For our product to be successful it had to be able to make that transition between forward and reverse, easily. It had to be as smooth as silk, just like it would be on a Moviola When we were done, you could take the joystick and move slowly through viewing frame by frame or move very quickly in forward or reverse. It was tough work, an extremely involved process.

Beeson had crafted a device that used non-timecode U-matic decks. The ECS system derived its accuracy from counting control track pulses from standard videotape. While it had been a technical limitation that Convergence had overcome, it also became a sales point. Buyers didn't need the comparatively expensive timecode generators and readers to support the ECS-1 and Christensen's publicity material read:.

ECS-1 Joystick Editor provided, for the first time, film style editing flexibility.

The timing of Convergence’s release of the ECS-1 system was near perfect, despite having lost the initial race to the CMX System/50. It emerged as the ENG (Electronic News Gathering) workflow was being adopted by hundreds of television stations worldwide. Editors who were unaccustomed to video systems found the ECS-1 relatively easy to learn and it became an immediate hit. Gary Beeson explains:

We included E to E switching, so that the editor could see the playback and record machine on one monitor. And we added all sorts of electronics to make it accurate because there wasn't any timecode. But the really tough work was in re-engineering the Sony decks that had really been designed as home video recorders. We had to basically go in and 'butcher' or pull apart brand new Sony machines because those first decks were not capable of reverse playback of tapes and the film editors were used to going back and forward, back and forward on their film editing systems.

Beeson recalls:

I’m sure Morizono; the head engineer at Sony just hated me! Here we were making a great business out of tearing apart his brand new ¾” machines and throwing away the official edit controller. But it didn't matter, it got us started and we grew to be the biggest of our kind very quickly.

Christensen recalls the success:

From the day we demonstrated our first system, we literally owned the low end of the market. I mean we had something like 25% of the total world market share in the non-timecode editing control systems for the next decade. After we had a successful NAB and we had orders flying in, so we had good cash flow.

The other key to Convergence's ability to create an editing market was that it aligned itself heavily with Sony's American distributors, providing them with conversion 'kits' and training for the modification of the hugely popular 2850 decks. The dealers were barely able to keep up with demand for a low cost broadcast editing system using Beeson's schematics and drawings and ECS-1 consoles.

As Beeson and Christensen had predicted, the U-matic format was going to create a wave of change in editing. David MacDonald later told SMPTE in his 'Beyond ENG' article.

It is now evident that one main reason that ENG succeeded so rapidly in the marketplace is because ENG methods are so similar to film methods. The people who were responsible for collecting and editing the news did not need to throw away the old skills and start at the beginning.

SPIELBERG AND KAHN

Steven Spielberg had created a motion picture hit with "Jaws". While the film had been edited by Verna Fields, the young director turned to Michael Kahn to edit his next film, "Close Encounters of the Third Kind". Kahn told Trevor Hogg about editing the science fiction picture through 1976.

We lived in the same house in Mobile, Alabama, and the editing room was in a really big playroom. I felt like a wife in a way. He went to work shooting the film. I stayed home and was cutting the film. I had this reel on a spindle [on the editing bench] and it got stuck; I couldn’t get it off. I had just started working with him and I said, ‘Maybe you can help me get this off.’ And he pulled the spindle off. It was so funny when I think about it. He just hired this guy who couldn’t get the reel off the spindle!

Kahn had worked as a television series editor on programs like "Hogan’s Heroes".

Everything I did in television prepared me to work with a guy like Steven. He moves quickly but…he shoots a lot of coverage. “Steven has said on many an occasion that he shoots film for the editing room. He gives us an endless amount of options.

The Kahn and Spielberg editing relationship lasts to this day.

TAO AND CMX/50

With sales growing Convergence moved from their tiny office on Redhill Drive, into a 2000 square foot industrial space on Sky Park Circle, near the Orange County airport. By the SMPTE meeting in Los Angeles, the Convergence team had grown from two to over 50 employees. Within a year the staff count had gone from 5 to 100, one of whom was Doug Tao. At the age of 14, Tao had built a black and white TV camera then learned television production techniques at high school before attending UCLA School of Engineering.

I had friends who took Communication courses and they were always broke and hungry. I made a decision to pursue the Electrical Engineering (EE) field and eat regularly.

After graduation Tao worked as a writer/producer of technical training tapes at Sony Broadcast. With the success of its more affordable U-matic machines, Sony released a new U-matic machine, the BVU-200 and a new editing controller, the BVE-500. At the same time CMX released a simpler version of the System/50 called the System/40:

…computer-managed video editing system designed specifically for Electronic News Gathering.

The System/40 (above) was designed to make cuts only and was stripped of the System/50's special effects capability. TV stations could buy a basic package that included a computer, CMX software, interfaces for two U-matic decks and over time add more machine control, a vision switcher and software to handle A/B roll dissolves. The proliferation of cheap cameras, efficient edit controllers and affordable videotape machines changed news editing forever and also spawned a new era in post-production. Steve Michelson left TVA to create One Pass Inc., with Buck Lindsay.

The ¾” format was the first helical technology to make the cross over to broadcast use and combined with the TK 76 camera it was a hot combo. Our phones never stopped ringing from the time we started with one employee, Jim Rollins. It grew to become the largest post production studio in the Bay Area. When One Pass started the world was still editing on 2" technology and we were among the first to originate on professional ¾” and that was just the start.

One Pass became San Francisco’s finest ‘graduate’ school for video editing.

We started with a CMX-50 offline editing system for cassette to cassette editing and found ourselves in Hollywood at one of the major studios every week doing the finishing work.

Editor Rod Stephens recalls:

Electronic editing was starting to concern our Editors' Union Board and as a result we contacted CMX and contracted to buy one of their CMX-50 off-line systems and start giving instruction to our editors, subsidized by the Guild.

The team at Ampex was readying a machine that revolutionised post-production in facilities, like One Pass. Mark Sanders presented the Thor 2 videotape machine and TBC to management. The new machine, now called the VPR-1, could do everything that 2” VTRs could do and more. Sanders recalls:

(Charles) Charlie Steinberg was amazed at the VPR and immediately realized the implications for not only the existing 2” quad machines but also the new AVR-3 to be introduced at the upcoming NAB show in Las Vegas. He knew its positioning would have to be handled sensitively to protect the existing Quad product line.

Ampex had 70-80% of the world market in professional recorders, almost exclusively on 2” (Quad) machines, but it had internal problems. In the company's California labs was the yet-to-be-released AVR-3 that had cost thousands of dollars to develop but an unoffical group inside Ampex had created their own videotape machine that made the AVR-3 redundant. Jim Wheeler recalls:

I was called into the office of the Video Marketing Manager and he emphasized that THOR must not be a professional product. We were ‘not to compete with the Quad machines’. Quad was Ampex’s bread and butter and as a result, we cheated in a few areas. For example, we used torque motors instead of pancake motors for play and rewind and we had a professional engineer design the Control Panel.

Mark Sanders recalls the VPR-1’s positioning.

We went back to the helical group and I created a profile of the VPR-1 that understated the picture quality and sold the other remarkable features such as slow motion as a low-cost complement to Quad and a natural fit for sports and industrial broadcasters..

Steinberg and Ampex product manager Arnold Taylor addressed another problem. They needed to sell the AVR-3 as part of a comprehensive package that included an editing device, otherwise Ampex would continue to see their customers buying IVC videotape machines to team up with Datatron, TRI or CDL editing systems.

The problem was complicated by the fact that Ampex only had the awkward RS-4000 editing system or the ageing Editec edit controller to sell. Neither device was capable of keeping up with the new AVR-3 and its tape shuttling speeds. NAB was four short months away so Ampex turned to Central Dynamics in Canada. Ken Davies recalls:

Although there was a successful division at Ampex making tape drives to support computer technology, the Broadcast division was never really interested in applying computers to video editing. Of course they saw that CDL was selling the PEC-102, which was driving videotape recorder sales. The new system called EDM-1, was essentially a specialised version of the PEC with a new front door, a new console and extra features on the switcher but it was basically a PEC-102 with an Ampex badge.

COPPOLA, BVU AND EDM

Hollywood filmmaker Francis Ford Coppola was no stranger to the limitations of film based editing or the lack of advances in an electronic equivalent. He and his editorial team had logged and edited 800,000 feet of rushes down to a 2 ½” hour final cut for the film The Godfather. As 1976 began, Coppola started shooting his next film Apocalypse Now in the Philippines. CMX Systems chief Bill Orr connected with Coppola who had been previewing dailies on Betamax cassettes to discuss what equipment CMX could create for the director.

He was interested in technology and a better way to edit so I got all my vaccinations for the Philippines and a few days before I flew out the production company called and told me that they had closed down the shoot due to bad weather, hurricanes and so forth.

Coppola planned to use a CMX prototype on his return.

As the engineers at CMX contemplated what could be built for Coppola, the designer of the original CMX 600/200 took a bow. Adrian Ettlinger was honoured at the New York meeting of the Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers. He was presented with the David Sarnoff Gold Medal for his contributions to electronic editing at a time when CBS still wanted an electronic version of the Moviola. CBS group president John Schneider mandated that more of the network’s sit-coms be recorded on videotape and he wanted the modernisation of editing to follow. Schneider told the press:

“We will need an electronic editing device; something to handle the 300 to 400 edits presently made in each hour-long program by a Moviola.”

The need for a non-linear editing system still existed.

VPR-1, EDM-1 AND TR-600

The 1976 NAB show in Chicago represented the past and future for Ampex and perhaps videotape overall.

Alongside an original 1956 quadruplex machine stood the original Ampex team of Msrs. Ginsburg, Maxey, Pfost, Dolby and Anderson to witness the launch of the latest 2” Quad machine - the AVR-3. Ampex also introduced a brand new computer-aided editing system called EDM-1.

The $95,000 system consisted of a stand-alone console that incorporated a video switcher, monitor, edit decision display and keyboard. The EDM-1 used a PDP-11 mini computer with 8-inch floppy drives for I/O and a DEC writer for hard copy. It could store up to 3200 edited sequences and was able to not only store and recall shots using timecode but it also had an 'exclusive' system that permitted individual scenes to be identified with 'real language'. In reality the EDM-1 was a modified version of the PEC-102 that Central Dynamics had first created in 1971. CDL's Ken Davies recalls:

Up to this point videotape machines did not have built in capabilities to read time code, cue to edit points and to synchronize machines together. All this functionality was added on to the machine by the tape editing system vendor. The new AVR3 (Ampex's last Quad VTR) had a built-in timecode reader and cueing capability. The machine could be given a cue point and it was able to go into Fast Forward or Rewind and then slow down and stop at the cue point.

The EDM-1 included key features that improved it from the ageing PEC-102, ones that were welcomed by linear editing bay editors. The EDM-1 had a ‘learn’ mode that allowed the editor to create effects, modify them and repeat them before committing to an edit. The software also allowed an editor to change a single edit's parameters and then 'ripple' the timecode shift on all subsequent edits. The EDM-1 automatically calculated the change in the edit decision list. Ampex hired veteran editor Art Schneider to demonstrate the system at trade shows.

Although my training before NAB was limited, I absorbed enough to be able to do the demonstrations needed to sell this kind of editor. It (EDM-1) was a classy piece of equipment and impressed me with its compact design.

The AVR-3 and EDM-1 were pitched as 'the perfect marriage' for those wishing to edit videotape and there were sold into editing suites in South Africa, Austria, Yugoslavia, UK, US, Australia and Canada. Editor Bob Glover recalls:

While it was built to sell Ampex's AVR-3, we were not as lucky as some and had 2 x AVR1's as players and a VR2000 as a recorder. There were numerous problems with the system such as horizontal edit shifts but the hardest part of using the EDM was the fact that we were in Australia and CDL was in Canada. There was the time zone difference and we only had the phone or telex to communicate. No fax, no email. Therefore, I would get to work around 4am to receive the latest suggestion from CDL, try it out during the day and send a reply back in the afternoon.

Not without some irony the AVR-3 was launched as the ‘best’ Quadruplex machine released but it ended up being the last 2” quadruplex machine.

Ampex’s own Thor 2 team debuted their new 1” helical scan machine at NAB.

The VPR-1 had the ability to deliver high quality video but it was the AST (automatic scan track) system that delivered instant slow motion playback that stunned attendees. Jim Wheeler recalls:

The VPR was the hit of the show. Sony also introduced its first professional 1” machine but it did not have the Instant Replay feature (the AST) that the Ampex VPR had.

The fact that the VPR came with a built in editing controller and had fast transport shuttling times was lost in the demonstrations.Sony also released new videotape machines with its the BVH-1000 1” helical scan machine taking centre stage. A similarly secretive group of engineers had built the BVH from the ground and it used Sony's new Omega Recording Method. The promotional literature promised much:

Sony video engineers set themselves a challenging goal: to create a production video recorder capable of duplicating the film feeling top creative editors want, without sacrificing any of the electronic advantage of video editing techniques.

Sony expected to start delivering the $69,000 BVH-1000 within months:

We'll have the production version of our new 1" high band video recorder, the BVH-1000 within 60 days.

Sony also debuted bi-directional hardware for editors called BIDIREX that it called:

Sony's answer to Moviola type film editing.

Editor Lance Trimington recalls the technology.

The Bi-directional controller, or BIDIREX dial as Sony sold it, allowed editors to shuttle and jog their videotapes at speeds between 1/30 to five times giving the editor some semblance of a film flatbed's feeling. But the 1000 only had standard SMPTE timecode and a mechanical tape counter. It would take the arrival of VITC and an updated BVH for the Sony machine to become widely used in editing suites.

While the 1” machine and its new editing controller were significant developments for online video editing companies, the other announcement from Sony at NAB proved to be decisive in the adoption of ENG and low cost editing. After working around the clock to meet Flaherty equipment brief, Sony also released the Broadcast Video U-matic (BVU) format and two machines, the BVU-100 and 200.

The BVU’s video wasn’t comparable to the newly released BVH-1000 1" but it was more than sufficient for newscasting and as Flaherty had dictated, comparable to 16mm film image quality. Sony’s Doug Tao recalls:

Although the BVU-200 was, in reality, a souped-up VO-2850/2860, it also provided bi-directional variable speed playback.

Alongside the BVU decks Sony also launched the BVE-500 automatic editing controller. The 500 was described as the 'companion editor' to the BVU decks but was limited in its operations because it was tied to the decks' technology. It could only use the ‘discrete speeds’ that it and the ¾” deck could accomplish together.

Tao adds:

The 500 and its decks, only had four forward speeds (1/20, 1/5, x1 and x2) by selecting a row of buttons and reverse was a mode that had another button. The 500 console provided dual digital tape counters, forward and reverse play at normal and 1/20th speeds, edit preview and edit point memory control but it did not use time code nor have any edit list storage capability and it was non-computerized

Despite the limitations, the package was well received by broadcasters. CBS News and 60 Minutes staffer Steven Smith recalls:

The BVUs were pretty reliable machines. When you hit the Edit buttons, the BVE controller would backspace both machines, lock them up, release them and make the edit. The sound a proper edit made was most reassuring. Big solenoids in the decks provided the noise. First there would be a slight “clunk” (reversing the transport).Then there would be a good, solid “kathunk!” (the solenoids kicking in). That was followed by a another slight “clunk” and sometimes a tiny “screech” (the transport stopping and the tape slipping). Another solid “kathunk” indicated the switching of the solenoids to forward. Finally, at the inexact edit point there would be a barely audible “click.” Any deviation from this sequence indicated a glitch that might or might not grind the editing process to a halt.

Even though the new BVU decks had a more flexible approach to playback, the BVU’s editing controllers were not yet fully designed for editing.

The Convergence Corporation once again sensed an opportunity that Sony seemed to have missed. If they could let an editor ‘toggle’ the ¾” decks at speeds other than those set in the original design, it seemed to follow that they could deliver a more tactile interaction, much like a Steenbeck or KEM. Doug Tao continues:

(All of the) systems were similar to each other, Television Research International’s systems or the Sony’s edit controllers but Convergence approached it differently. They introduced the human-machine interface of the joystick, which no other system used.

Ampex and Sony had dominated the NAB conference but others also debuted new editing systems. The once powerful RCA Broadcast Group from Moorestown demonstrated its new tape machine and allied edit controller.

The TR-600 is built to deliver performance that equals or surpasses any broadcast quality quadruplex VTR, regardless of cost.

Alongside the new VTR was RCA's AE-600 editing system and press statements read:

AE-600: the only integral VTR Time Code editing system. The new technology RCA TR-600 videotape recorder now offers the AE-600, a complete Time Code editing system contained inside the recorder. It's an industry first.

The press release promised:

...the operator with total flexibility for expanding artistic creativity. It minimizes the technical non-creative delays normally associated with editing systems.

The AE-600 unit could control a single record VTR along with eight playback VTRs and could be programmed to handle split audio edits, video only events as well as audio/video edits automatically. The AE-600 achieved this as a result of RCA's own research into large-scale integrated circuitry and advanced microprocessor and programmable memory devices.

JIM ADAMS

Meanwhile in a corner away from the major NAB displays was ex-CMX engineer Jim Adams with his own computer controlled editing system. Mach One, named for his 1969 Ford Mustang model, was designed to control a group of videotape machines to perform linear editing in tandem with a vision mixer, audio desk and character or title generators. The new editing device naturally did many of the things that Adams had helped program into the original CMX 600 and then a few of its own. The Mach One system was able to ‘group’ or ‘cluster’ edit functions (fade up, title fade up, dissolve video, fade out title) as a single event instead of multiple ones.

Adams was one of only a few independent software and hardware engineers who understood editing and computing. With lower overheads he was able to deliver personalised editing systems that could control multiple VTRs and text devices, like Vidifont, below the price of the dominant CMX. Soon companies like Tele-Color Productions in Virginia and Trans-American Video in Hollywood were using either a suite from Mach One or CMX/Orrox.

The 1976 NAB show closed with consensus that Ampex and Sony had delivered huge changes for videotape and electronic editing. The VPR and BVH had effectively ended the reign of 2” Quad recording started by Ginsburg in 1956. Tom Werner recalls:

Sony, a very large manufacturer, developed their rabbited guide, a special machining process that provided a highly precision tape guide on the scanning drum surface. Ampex developed an electronic solution, the Dynamic Scan Tracking head that could provide interchange under almost any kind of tape position around the head. DST also provided a broadcast quality freeze frame or slow motion, which was a huge development. Thus it made clear the mind set and strengths of each company. Ampex electronic cleverness and innovation, Sony able to manufacture extremely high precision tape handling very cost effectively.

The 1" VTRs opened up a new set of issues as Jim Wheeler continues:

The three U.S. TV networks did not like the possibility of two different videotape formats. After all, they had 20 years with a single format, so they asked SMPTE to develop a compromise format.

The SMPTE standards committee settled on a common video recording format that both Ampex and Sony could accommodate with their BVH and VPR recorders. The two manufacturers competed to re-equip broadcasters worldwide with their respective ‘C’ format machines. Werner adds:

We had some of the very first BVH-1000s at One Pass Video in San Francisco and quickly understood that BVH stood for Big and Very Heavy.

CBS executive Joe Flaherty spoke of the BVH-1000’s editing credentials at the 10th International Television Symposium in Montreux.

These machines promise to make videotape off-line editing systems at least as flexible as film and to finally close the videotape editing gap.

340-X

CMX was already selling the CMX Edipro/300 editing system capable of offline and online editing. That system allowed editors to start and finish a project with one system using a traditional keyboard interface and it had become a runaway success. With the launch of 1” machines, Bill Orr decided it was time to update the CMX-300 and create the CMX-340x.

As you can imagine, good engineering was vital to the success of CMX. We got to the top and stayed there in large part because of our outstanding engineering staff.

Under Stanley Becker, CMX began the transition from the ageing DEC PDP 11/15 series minicomputers that used core memory to the new PDP 11/04 using LSI chips. The newer PDP computer was easier to debug for programmers and better suited to real time applications such as controlling videotape machines.

As a result the 340x was a modular device that could be expanded from a two VTR configuration set-up to a major online bay with more than 20 source machines. The new 340x editing system had a 133 key color-coded keyboard and a jog/shuttle knob called Gizmo. By adding a streamlined hardware interface, it was hoped that the new system could be more flexible to operate. Despite the modernisation of the core hardware and user interface that editors could see and appreciate, the 340x was to have an engineering innovation hidden away in the machine room that set it apart from its competitors. Bill Orr recalls:

In those days, interfacing with the myriad of videotape devices that came to market and needed to be included in new editing systems was not so easy a job. The real problems for CMX were the new video machines, reading the time code at high speeds during fast-forward and rewind.

As a workaround to the ‘interface’ problem or getting editing systems to talk with different tape machines and devices, many post-houses transferred material from the various format tapes to a common tape format for editing. Tom Werner recalls:

CMX was very aware of the Compact Video editing system built by Sayovitz and Matz and in my opinion it played a part in the inspiration of the CMX-340x.

Gene Simon and Carl Labmeir solved the interface problem with an Intelligent Interface Unit or I2 . The I2 unit sat between a specific device on one side and the editing system on the other. When an editor instructed the 340x to control a device such as a tape machine or vision switcher, the I2 made a real time interpretation between the two and displayed all machines as being the same. The late Jack Calaway put it thus:

The I2 was an elegant solution to a major problem. Most of the available VTR's required parallel control and external time code readers. The same was true for the video switcher and audio mixers. To deal with these hardware differences, each I2 was designed to control a specific VTR or switcher. A brilliant solution to a knotty problem.

Gene Simon recalls:

Stan Becker made it a requirement for us to use an industry standard RS-232 interface between the computer and the I2 interfaces. We used the PDP 11/04 with some CMX added boards for a real time clock (RTC), RS232 communication to the I2's and a bit mapped video card. All of which were designed by Carl and I. The Intelligent Interfaces approach was a big breakthrough because the device specific software now was no longer in the central computer, which made configuration management much easier.

Bill Orr recalls:

What CMX did, primarily through the engineering efforts of Gene Simon, was to build individual amplifiers to track the time code. In some instances, I don’t think they allowed machines to run flat out; in other cases, I think they estimated where a machine would be after n-seconds of rewind or fast forward, then slow it down to a readable speed.

The new CMX system was able to control a myriad of post-production devices and therefore allow an editor to create sophisticated sequences. It had progressed the use of 'look ahead' pre-rolling of VTRs and the time savings across the entire product were a marketing bonus for the sales team. Orr adds:

CMX was way out in front of whoever was second in terms of the various tape machines we could control in an editing system.

Despite the advances in its product line, CMX encountered other problems when it lost key members of the engineering team. Orr and Al Behr re-organised the company in time to ship.

We worked 10 to 14 hours a day, six to seven days a week. If CMX failed one more time, I’d be on the street. and I didn’t know who would hire me. Who wants the president of a failure?

Orr had long suspected that Sony could try to enter the on-line editing market but his competition came from American companies. The Convergence Corporation engineering staff began work on Superstick, a device to control the new 1” VTRs. Doug Tao continues:

This new microprocessor-based line of editing systems would embrace the use of SMPTE time code and produced frame accurate editing that could even do special effects using any combination of video tape recorders, be it U-matic or 1” format.

Gary Beeson recalls:

We decided that we would not only add microprocessor abilities to our ENG editing systems but we could make an editing system that was suitable for post-production, for the next generation of open reel videotape machines .

Convergence's Dennis Christensen recalls:

Our whole approach was to keep the editor’s mind on the program and allow them to worry about telling the story rather than on whether to hit the yellow ‘mark in’ or ‘mark out’ keys on a Qwerty keyboard. To keep growing sales you need to demonstrate the system to film editors but you know they’re totally intimidated by a qwerty keyboard with yellow buttons all over it. So our systems were much more user friendly and we really established a tremendous following of very satisfied people who loved the ergonomics and the human interface and our approach to editing.

Convergence also released the ECS-10, a low cost model for editors wanting to buy equipment but unable to afford the ECS-1. Beeson and Christensen then reached out to George Bates, VP of engineering at Dynair. Christensen recalls:

In the beginning we weren’t established enough to get Bates to leave his job but after that very successful first year, he made the switch.

Nearby manufacturer Datatron released what it called ‘a new concept in videotape editing’ with the Tempo 76 Editor system (above). It featured a rotary controller called VaraScan that gave users access to slow motion, reverse and freeze-frame capability when teamed with Sony 2850 decks. It was pitched at film and older videotape editors who were unwilling to edit with the touch screen technology of Seehorn’s Lightfinger and Ampex ACE. CBS editor Dwight Morss told Broadcast:

The operator is only confronted with those specific instructions he needs at any one time in the editing process.

Editor Rod Stephens used the Tempo 76 to cut the ABC series, ‘The Greatest American Hero’.

APPLE COMPUTER

In an apartment in Milipitas, California three young men agreed to start a computer company. Steve Wozniak, Ronald Wayne and Steve Jobs co-founded Apple Computer Company which eventually made record sales of desktop publishing and desktop video tools but Apple had a far more profound effect on the careers of the next generation of computer programmers.

Xerox Corporation was embarking on a project at its PARC labs so profound that it defines computing to this day. Harold Hall, manager of the systems science laboratory, wanted someone to look at the company’s existing research on networking, protocols, programming techniques, operating system security, memory protection and user interfaces, then apply it to a new project. Hall tasked Dr David Liddle with building a team to:

...to harvest these ideas into a long-term architecture for Xerox’s entry into the new world of the automated office.

Liddle soon had Robert (Bob) Belleville, Robert Garner and Dave Curbow on board. Their goal mirrored Xerox chairman C. Peter McColough’s mantra from 1970:

...we wanted to induce people to produce subtle and elaborate documents that would then favor our ability to make money by storing and managing and printing them.

David Smith had received his Ph.D. from Stanford with a thesis that advocated the idea of computer icons and programming by demonstration.

Then I had to get a real job.

![]()

XEROX

Smith joined the SDD group and over the following years co-developed a group of technologies that defined computing. Their product, ultimately called the 8010 Star Office System, targeted office workers, as well as people who created, manipulated, analyzed and swapped information. Smith recalls:

Since Star users were to be office workers, it was obvious that we couldn't give them a standard command-line interface such as Unix's. These people had no interest in becoming computer experts and we couldn't expect them to take a programming class or Unix class before they could use the computer. If we couldn't bring the users into the computer's world, we would have to bring the computer into the office environment.

The first thing I did was to bring my idea of icons out of the programming world and into the office. Instead of variables and conditionals, I created icons that represented documents, folders, file cabinets, mail baskets, printers, wastebaskets, book shelves, etc. Basically I created an icon for everything I could think of in an office, but in all there were only a couple of dozen of them. Again the key characteristic was that icons have machine semantics as well as visual semantics. For example, if you dragged a document icon into a folder's window, not only would the document appear in the window but the computer's file structure would get modified. If you dropped a document icon on a printer icon, paper would start coming out of a physical printer somewhere, possibly in another city.

The SDD team built a modern computing interface, create unique hardware solutions and make the first inroads into multitasking architecture. The speed at which technology had pushed the engineers of the 1950s and 1960s now seemed glacial when compared to the weekly changes in the computer industry in the 1970s.

A chipmaking pioneer offered his thoughts on the future. Federico Faggin was responsible for the design of the first microprocessor and creating Zilog. He later received the National Medal of Technology and Innovation from U.S. President Obama in recognition of his work but at the time Faggin set out what he saw for the decade ahead:

By 1977, microprocessors were firmly planted in the world and were becoming part of the fabric of everyday technology. Computer clubs were sprouting up throughout the U.S. The number of young computer enthusiasts was increasing rapidly and with them came an enormous amount of creative energy, enthusiasm and exuberance.

GEEKS

Joe Rice, Nicholas Schlott, Chris Zamara, Stephen (Steve) Reber, Markus Weber and Tim Myers were typical enthusiasts of their generation who exploited the power of microprocessors. They created, refined and built computing products in their early careers and eventually helped define computer editing systems. Rice took a term off from MIT to look around at his career options and headed to Silicon Valley, landing a job with the Calma Company in Sunnyvale as a software programmer. Calma's best-known products were targeted at the integrated circuit design market.

I was 19 and shocked at how much they were willing to pay me. After the contract wound up, I returned to MIT and declared Computer Science as my major.

Nick Schlott was growing up in the suburbs of Chicago and had a taste for programming.

Of course this is in the days before anyone really had computers at home, so when I was in Junior High I used to cycle the five or six miles down to a local community college to use their computer terminals. I remember a favorite book of mine at the time was ‘My computer loves me if write in BASIC’. Another book that influenced me a great deal was ‘Computer Lib/Dream Machines’ by Ted Nelson, I remember seeing this book. I wasn’t sure what to make of it entirely at that age but it was unashamedly enthusiastic about computers and what they could do once they became widespread and after reading it, so was I.

Chris Zamara was born and raised in Toronto. He was a self-confessed ‘total computer geek from day one’ and started experimenting with electronics at the age of 13.

I programmed on every computer I could get my hands on, hacking well into the nights. I borrowed and built computers whenever possible and programmed everything from the first programmable calculators to KIM-1 micro-controller boards in machine code, building hardware interfaces when needed. My first home PC was built from a kit with a wired-on keyboard from a surplus store, custom-built power supply, extra RAM, etc. I used Commodore PETs (below) in High School and eventually acquired my own Commodore 64. Then when I started Computer Sciences studies at Ryerson University in Toronto we were entering programs onto punched cards and feeding them into IBM mainframes! It was a horrible experience for a personal computer hacker. We programmed in ancient languages like COBOL and PLC and it seemed like a history lesson into an era that was over and I didn't care about. I learned ten times more in my spare time with my various projects and contracts and jobs than at school.

Stephen (Steve) Reber graduated from Fairport Senior High, NY after computer studies.

I gobbled up every course that they had there. I just had a riot with it. It seems amazing now, but at that time it was pretty radical for a high school to have a computer that anyone could use, let alone students. They had penciled cards, single user, punched tape, Teletype, Basic language and a Hewlett Packard computer, probably the model 2115. That was my first exposure, thanks to our Math and Computer Science teacher, Mr. Motkowski. I decided computer science was the way to go, after looking at becoming an accountant or a draftsman. I took a few classes, but still at the age of 16 I realised they weren't me. Those industries were doomed, they were going nowhere and computers are going to whop everything!

Tim Myers was as an archetypal Southern Californian teenager who made home movies.

We had an 8mm camera and we would experiment with making stop motion movies in the street. That sparked my interest in film, video and photography. I learned that I had a fascination with the process both from a creative and engineering standpoint. As I got older, I really decided I wanted to be involved with building tools for the creative process and imagined one day that I would.

In Munich, Markus Weber finished high school and took an interest in personal computers.

The only ones available at all were Commodore PET machines with 8kB of RAM, which you could upgrade to 16 or 32 kB if you were an electronics geek and knew how to handle a soldering iron. Well, I wasn’t one of them, but a good friend of mine was and he actually owned one of these machines. We used it play games and I actually tried to port an algorithm for estimating pi from my 16 step programmable pocket calculator to the machine’s basic and failed miserably. It was an emerging field at this time, but I could not dream of anything more boring and I honestly despised all of my class mates who were seriously looking into this for doing this. I would not waste my time with such a “sub-standard” occupation.

In stark contrast to the working lives of engineers like Ampex’s Guisinger and Machein who had finessed hardware for editing, Schlott, Zamara, Reber, Myers and their generation worked in an era when software assumed that role. The young programmers extended the new found capabilities of computing to desktop video and in doing so, redefined the parameters of what editors did and what editing was. By a twist of fate the lives of two key players in electronic editing crossed paths on the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) campus before working together. Joe Rice recalls Bill Warner from his classes:

Some of the required classes at MIT were in large lecture halls and I remember Bill as a guy a few years ahead of me who would sit in the front row of classes and raise his hand and ask a question in a room with 700 people in it. And say 'I didn’t get that?' in a manner that suggested 'you didn't explain that well!’ He was certain enough that if he didn't get it, it must have been because of the way that it was explained. Now he didn't do it all the time but I thought, 'Wow that guy isn't afraid to do what he needs to do'

Bill Warner recalls:

Most of the kids at MIT were first or second in their class. I wasn't. A lot of them had 1500, 1600 college boards and I didn't, so I was in all these classes with all these genius kids, these super study nerds, amazingly good at this stuff and I thought, 'You know what, there's no way I'm going to get through this, unless I stand out'. I mean, none of these people ever asked a question. They would go back to their rooms and try to figure it out later. I said, 'Well, what he said just doesn't make sense, so I would ask questions.'

While Rice and Warner were in MIT classes, Bill Kaiser had finished his studies and landed a job with Hewlett-Packard in Cupertino.

I was a kid who had grown up in Ohio and seen very little of the United States, except for Boston, so I wanted to move to the West Coast to work in Silicon Valley as an engineer. It was the big frontier, HP was THE company to work for and I was lucky enough to get a job with them.

A future colleague of Kaiser’s began work at the other computing powerhouse, Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC) in Maynard. DEC had been so successful selling microcomputers to the scientific and engineering communities over two decades that it was able to lavish an annual budget of more than $40m on R&D.

Curt Rawley began working in DEC’s Computer Systems Development.

It was just a fantastic place to work and I enjoyed every single day of it. The experience really formed many of my own personal values. DEC were building products like tape drives and minicomputers that were changing the industry and in turn people's lives. It was a unique culture where engineers loved to come in and build really good stuff. I became really infected with the hi-tech bug of 'can you build a better mousetrap', can you build something that customers are going to benefit from whether it be faster, cheaper, better, more capable.

Rawley used his experience at DEC to lead a world-class company that made a better editing 'mousetrap'.He joined Bill Warner, Joe Rice, Steve Reber and a small group of engineers to create a product that changed editors’ lives.